Leslie Willcocks, London School of Economics and Political Science.

In our last newsletter we highlighted how organisational politics are not aberrant, but form an inevitable part of technological change, and therefore need to be managed, as far as this is possible, by the interested parties. I have been either participating in or researching IT-based change since the early 1980s, and find that the techno-politics of those early attempts to bring computers into the larger organisational area, is dwarfed by subsequent developments as information and communications technologies have advanced and become ever more pervasive joining up every aspect of both our social and work activities. This has brought technology out of the specialist hands, so that it touches and impacts multiple organisational and external stakeholders. Not the best time then, to proceed unilaterally, as if everyone is on board with your plans for automation and digital transformation.

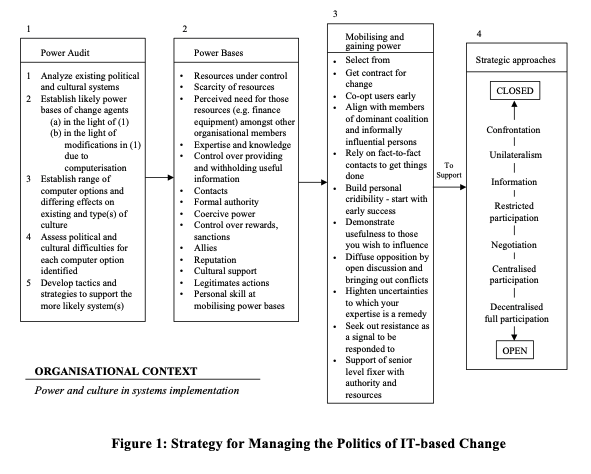

The politics of technological change is, of course, a massive area, and in this article I am choosing to treat it only at the organisational level, and from a management perspective. For those wanting a broader, macro view, please see the last chapter of our book Service Automation: Robots and The Future of Work (SB Publishing, 2016). My intention here is only to offer a more organised way of thinking about how to consciously manage the politics of technological change. The suggested approach, which has emerged from looking at several different waves of technology, and thousands of cases, is shown in Figure 1. Throughout, I will use the word ‘technology’ to cover computers, ICT, automation and digital technologies.

The Power Audit

A first step is analysing the existing political and cultural system of the organisation. This means establishing membership of the dominant coalition and the sources of their influence. It also requires close analysis of lower-level participants, their power bases and the manner in which they, as well as the dominant coalition, are likely to support or resist any level of technology adoption, and how crucial such responses might be to system development and implementation.

A second step is establishing the likely power bases of the change agents in the context of the existing political and cultural systems. Also, how these power bases can be modified in the course of implementation.

The third step is to establish a range of possible technology options, and their differing effects on the existing distribution of power. More radical shifts in power distribution will require different strategies and alliances, and a much more meticulously derived political approach.

The fourth step requires an assessment of the political and cultural problems likely to be engendered in the course of developing and implementing each of the technology options identified. A preliminary assessment of the political feasibility of each proposed system can then be made.

The fifth step is to develop strategies and tactics to support the more likely systems and make an assessment of how successful differing combinations of systems, tactics and strategies are likely to be.

The power audit assists change agents in understanding the existing power structure and culture, who is influential, who will resist different types of system, who will be affected in what ways by different proposals, and how different change strategies will be affected when different individuals and groups mobilise their power. It will end with an understanding of the political complexity of automation and digital transformation, but also a clearer idea of the political feasibility of different types of system, design methodology and change approaches.

Mobilising / Gaining Power

How can influence be managed? Political goals need to be formulated, and an ends-means analysis carried out (i.e. what do we wish to achieve, and how do we go about achieving it?). Targets to be influenced are then identified, and incentives desired by the targets determined. Implementation involves mobilising these incentives and monitoring the results.

The management of politics and culture must continue throughout the technology project. In organisational settings, a political approach is rarely just a matter of accumulating enough power at the beginning of a project to do what you like thereafter. Various approaches to influencing the process of technology implementation are possible. Peter Keen, as long ago as 1981, suggested that the IT function be headed by a senior-level fixer with resources and authority to negotiate with those affected by any new system. A steering committee including senior-level managers could become actively involved in highly political aspects of the technology project. Under this umbrella, those responsible for managing change can establish credibility and influence events tactically:

- • Make sure you have a contract for change.

- • Seek out resistance and treat it as a signal to be responded to.

- • Rely on face-to-face contracts.

- • Become an insider and work hard to build personal credibility.

- • Co-opt users early.

Other tactics might include presenting a non-threatening image, aligning with powerful others, developing liaisons, developing stature and credibility by attending to stakeholders’ immediate needs before gaining approval for a less well understood project, and diffusing opposition by open discussion and bringing out conflicts. Certain power resources can be mobilised. A crucial one is expertise. Change agents can increase stakeholder dependence by heightening uncertainties to which the application of their expertise would be a remedy. Internal consultant activities across departmental boundaries may give privileged access to, and so control over, organisational information. Political sensitivity and estab¬lishing relations with those with power is also important, as is the gaining of 'assessed stature' by identifying and serving the interests of relevant others. Group support by departmental colleagues and related groups is a further power source that can be developed.

Implementation Problems

- Techniques for reducing resistance to change include:

- • the need to make visible any organisational dissatisfaction with present systems

- • addressing people's attention to the consequences of not bringing in the technology

- • building in rewards and reasons for people to support the transition and the future system

- • developing an appropriate degree, level, and type of partici¬pation for different affected parties

- • giving people the opportunity and time to disengage from the present state

- • setting up temporary structures to maintain control over the project in the transition period.

Keen's recommen¬dations above are relevant here. Also, adequate planning and resources are needed to see the transition through. There is also the need to develop and communicate clear images of the future to organisational members, and establish multiple and consistent leverage points, aimed not just at individuals but also at social relations, task and structural changes. It is also important to build in feedback mechanisms to monitor developments as early as possible.

Keeping power on the side of the technology-enabled business project and handling the power dynamics of change is crucial. There are several activities that need to be kept in balance. Leaders and key groups will maintain active support for change, a culture and climate of success must be created, but also enough stability must remain. The pace of change has to be judged, so that the changes remain acceptable to involved parties. The selection and implementation of a strategic approach is also a crucial aspect.

Strategic Approach

'Contingency' implies retaining a flexible approach to technology implementation and building in opportunities to modify design where it is seen to be deficient. A contingency approach also means adopting a change strategy appropriate to the organisational circumstances in which those responsible for implementation find themselves. Such a strategy involves intervening in the technical, political and cultural systems of the organisation at one and the same time.

Change strategies range from being closed to open (see Figure 1). Closed strategies are marked by a minimum of communications and consultation, negligible participation in design and implementation by the vast majority of interested parties, and the development of systems by technology specialists to achieve managerial objectives, which tend to be control- and finance-focussed. Closed strategies are linked closely with the introduction of centralised technology systems. Closed strategies are often linked with confrontational labour relations, though this is not a necessary relationship, and depends on the power realities pertaining. Often these mean that little confrontation is necessary and the system is introduced unilaterally by management, systems professionals and contractors. This may be a sensible approach where the system is technically sound, and designed to minimise dependence on user skills and co-operation, or where organisational culture supports autocratic management styles.

By 2021 such closed strategies may be much less appropriate for most technology-based business projects. More open strategies stress participative design, communications, con¬sultation, and willingness to modify technical systems, job design and work organisation in the face of user feedback. Open strategies tend to be associated with negotiated change by agreement and consultative machinery in the labour relations sphere. Some strategies are more 'open' than others. Prototyping and ‘Time Boxing’ tend to be closely linked to open change strategies. Clearly, one best change strategy for all circumstances cannot be advocated. Open strategies are more relevant where there is underlying support for the aims of the project, where there is a large number of affected parties, where there are differing views on how, for example, digital transformation can be achieved, where power to resist introduction is widely distributed, and where user involvement will provide vital information for system development. Closed strategies will tend to be preferred where the benefits of participation are low, where there is widespread agreement and support for technological change, where the promoters of the system are all powerful, or where the level of disagreement and hostility about the system is so high that participation is perceived to serve little purpose.

Conclusions

Where dependent on traditional systems design methodologies, technology project management continues to be technically oriented, with human issues perceived as mainly arising at the implementation stage. Furthermore, implementation itself has often been viewed as a discrete 'one-off', late event in a technology project. The failure to consider many human issues as significant until late in the project means that when they emerge there is often a reluctance amongst implementers to adapt, let alone abandon, the technology system in which so much time, money and labour has already been invested. People and change management as an essential and primary implementation task then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy with a vengeance, with human issues and problems, and lack of user acceptance, persisting throughout the system's subsequent use.

A key task, then, is to manage behaviour and politics as intrinsic parts of technology-enabled change from the beginning. From a project and change management viewpoint, this means ensuring that the system becomes politically acceptable enough to be used effectively, and that a culture exists to sustain its continued use. However, technology will only form part of the overall change process. In earlier newsletters we have discussed how delivery of business and technology strategies require a holistic approach to managing programmed change. However, I would like to point out that the principles outlined here would seem to apply to all change projects in contemporary organisations. Politics do breed in times of change. The politics or ‘shadow’ track is planned for and followed, or managers find their way there by chance, unexpectedly, and invariably under less favourable circumstances.

Reference

Keen P. (1981). Information Systems and Organisational Change. Communications of the ACM, 24, No. 1.