Dr Leslie Willcocks

Introduction

I have been working with Dr. John Hindle at Knowledge Capital Partners on a series of papers based on research into the strategic use of intelligent automation. We are looking in particular at automation leaders in five major sectors—banking, insurance, telecommunications, healthcare and utilities. In mid-June 2021 we reported on selective findings and John also interviewed Janka Coppens, Managing Director of Intelligent Automation at ATB Financial—whom we discovered as a leader in this field. Elsewhere in this month’s newsletter we make available the link to that 58-minute video.

Our research findings are very rich—and it’s still work in progress. But I would like to report on some headlines here, since we believe there are important implications for senior executives in any sector, if they are to secure the immense business value that can be released through the effective use of intelligent automation.

Intelligent Automation: Top-Level Finding

A top-level finding is that there is indeed an immense amount of business value available. The surprising corollary is that a vast amount of it is being left on the table. I will try to explain what seems to be happening. Practitioners will be all too aware of what I call the technology-exploitation gap—technology advances faster than our capacity to use it. This is such a fundamental phenomenon that I will, next month, develop the theme and the ramifications much further. For the present it is enough to note that RPA; intelligent automation (combining RPA with machine learning); NLP; image processing; algorithmic usage; and AI (getting computers to do what human minds can do) are, in terms of general business use, astonishingly way behind where the media and hype like to suggest. All this is understandable—it takes time to develop, implement and institutionalize, then exploit these technologies. But what can accelerate this process?

The Exponential Value Path

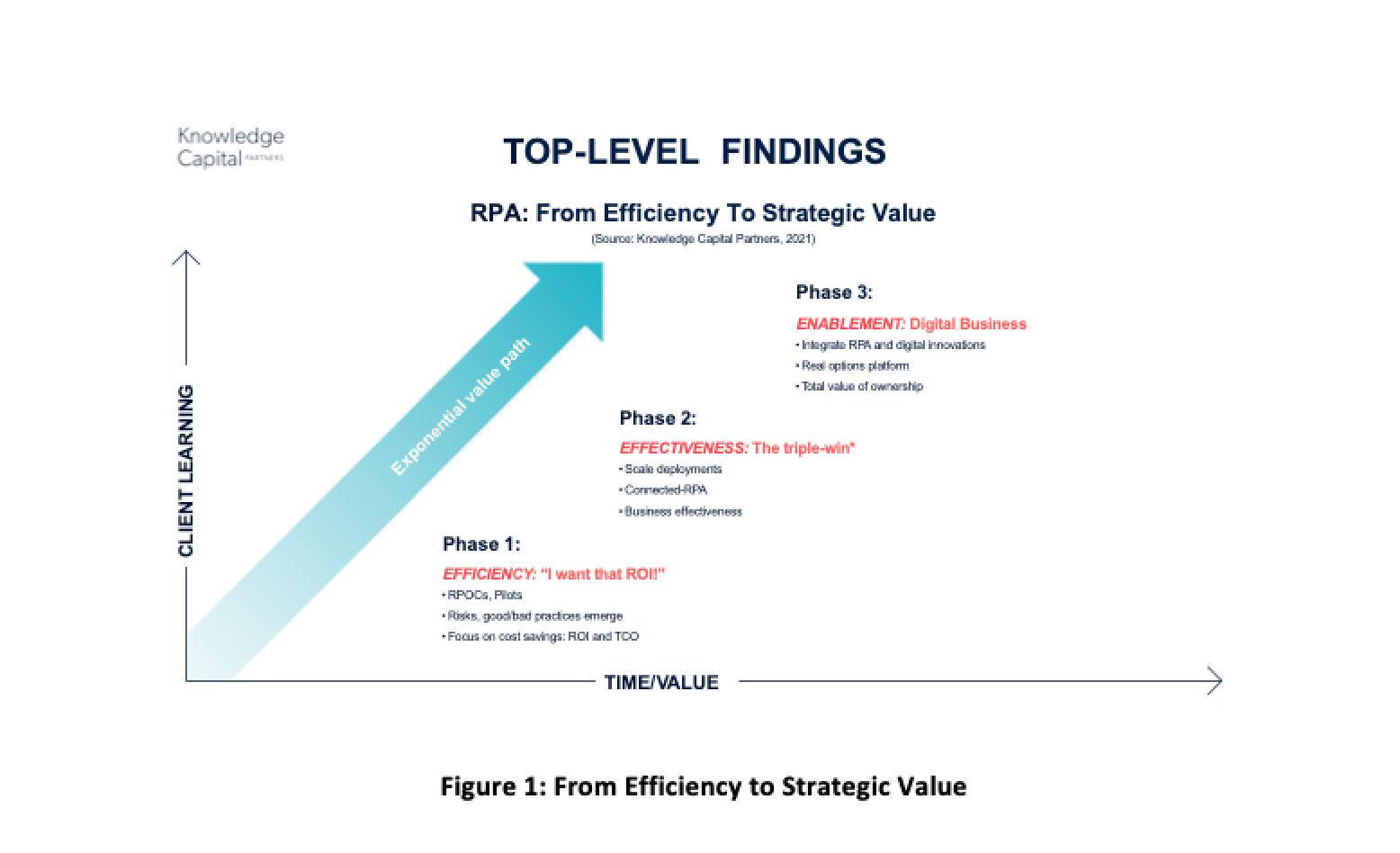

Let me suggest that part of the challenge is trying to understand the nature of business value that can be generated from applying these technologies. Executives are familiar with efficiency gains from technology, and using return on investment and total cost of ownership criteria to direct their technology investment. You need a different kind of thinking, however to get to the exponential business value that can be unlocked. Because, as Figure 1 shows, efficiency is not the end of the game at all—only the beginning.

With these technologies, business value is coming in three buckets. With each, the kind of value is different, and the business value increases exponentially. Figure 1 maps the evolution path some organisations seem to be taking with intelligent automation. Starting with ‘efficiency objectives’, they become more convinced by the technology, invest more, and then aim for ‘effectiveness’ then ‘enablement’ gains. Other organisations start with a much more strategic view looking for the end-point of creating an automation, then a digital exchange platform providing enablement gains. Other organisations, so far, have not got beyond the focus on efficiency, and/or do not see automation as a strategic investment. Let’s look in more detail at eight major findings to date.

Major Findings To Date

- 1. The potential of robotic process automation, even as a stand-alone technology, is vast and largely unexploited. Our studies of early adopters found examples of ROI between 30–200 percent in the first 18 months, and of ‘triple win’ shareholder, customer and employee benefits, many unanticipated. Yet, by 2021, the market is as small as $US3.5 billion, though estimated to grow at around 40 percent per annum for the next five years

- 2. Looking across the 54 plus RPA suppliers, most clients have between 1 and 50 ‘robots’ (licences). Few (13 percent) have scaled to 51–100, let alone a higher number. This has been changing in the last year, but reflects scaling, strategic investment and benefits aspiration challenges.

- 3. See Figure 1. The typical organisation gets caught in Phase 1. Initial outlays are small. Frequently the efficiency returns are good, but further investment looks expensive, and the benefits look less clear. With some vendor products enterprise RPA is harder to achieve technologically, and maintenance and support is costly. Looking at traditional ROI-based business cases, senior management under-invest, still seeing RPA—and indeed intelligent automation—as tactical tools. Digital transformation efforts maybe ongoing but do not connect up, being driven from a different place, with different budgets, and usually under-written from higher up in the organisation.

- 4. See Figure 1. The typical organisation gets caught in Phase 1. Initial outlays are small. Frequently the efficiency returns are good, but further investment looks expensive, and the benefits look less clear. With some vendor products enterprise RPA is harder to achieve technologically, and maintenance and support is costly. Looking at traditional ROI-based business cases, senior management under-invest, still seeing RPA—and indeed intelligent automation—as tactical tools. Digital transformation efforts maybe ongoing but do not connect up, being driven from a different place, with different budgets, and usually under-written from higher up in the organisation.

- 5. Our research re-discovered that for RPA, cognitive and AI automation, as for previous technologies, only 25 percent of the challenges are technological and 75 percent are managerial and organisational. This helps to explain the slow progress across Phases 1,2 and 3. Our four studies( ) showed 41 material risks arising when trying to introduce automation, but also established 39 management actions that not only mitigate those risks, but also lead on to effective business deployment. To put it bluntly organisations that operate in late Phase 2 and Phase 3 became good at managing risks and operating effective organisation practices.

- 6. The most recent research established also why Phases 2 and 3 are so difficult and why only 15–20 percent of organisations are doing well with digital transformation; and why, depending on sector and definition, 75–85 percent of digital transformation projects fail. Once again the challenges are mainly managerial/organisational, though getting a variety of emerging digital technologies integrated, deployed and institutionalised is a long haul. It could take most organisations today more than five years to become digital businesses.

- 7. Looking across our case studies, surveys, interviews and advisory work, we came to a stark conclusion: with RPA, cognitive and AI technologies, an enormous amount of business value was being left on the table. A great deal more value (at least 200 percent) could be extracted by hunkering down and applying RPA etc. much more widely for efficiency purposes. Still more value (the initial indications are 500 percent or more) could be gained by ‘hunkering down’ and looking for applications that gave business effectiveness. But our latest research suggests that the real value bonanza is in building a digital platform with automation and other technologies, that gives to the business flexibility, adaptability, strategic options and resilience at low cost. Initial indications here are that the value gained is exponential, exceeding efficiency gains alone by ten times (1,000 percent) or more. ‘Hunkering down’ is a profitable fork to take; ‘going big’ gets you much further, more quickly.

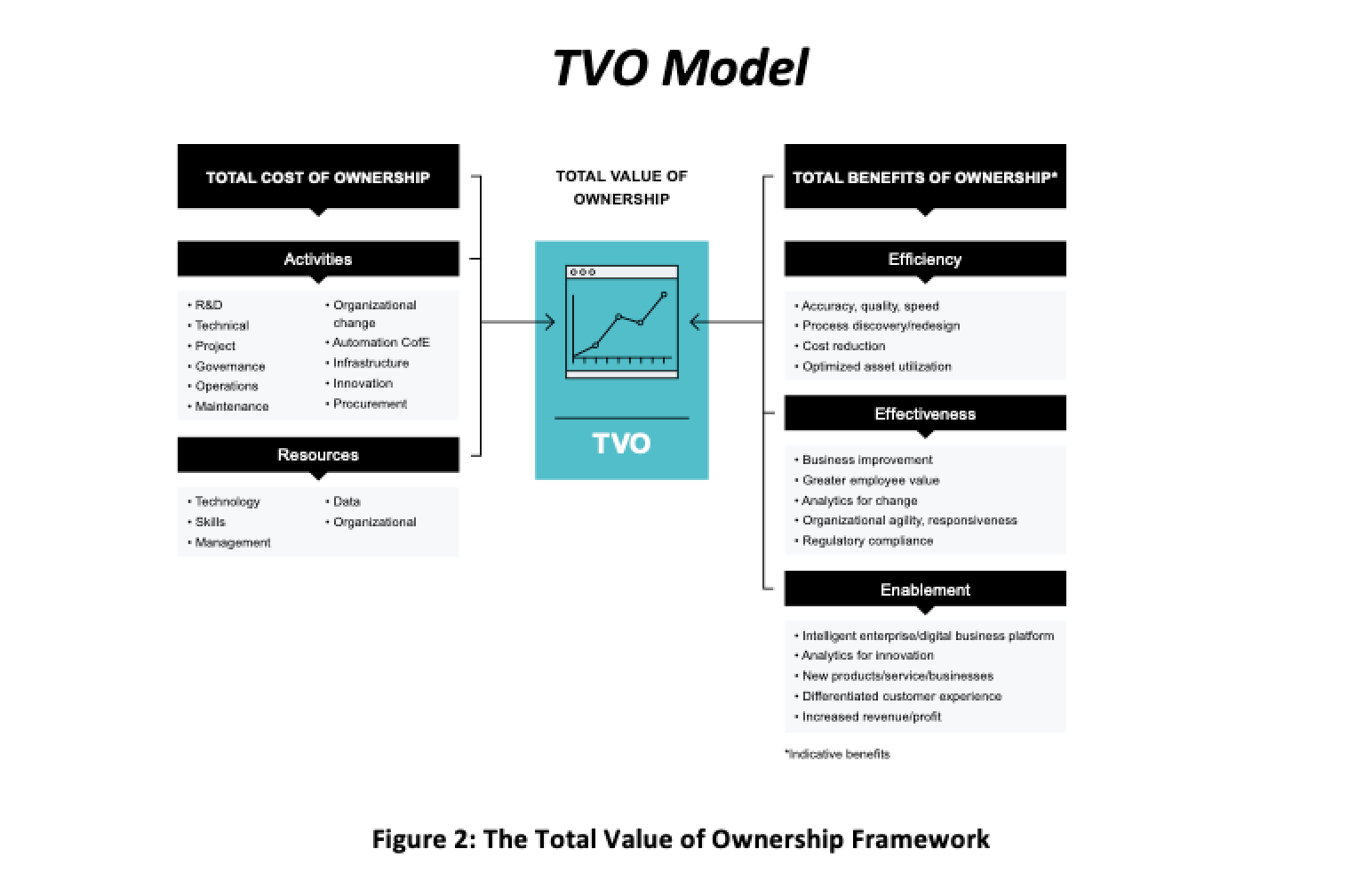

- 8. Finally, this made us ask: “Why is this value being left on the table?” What is noticeable and distinctive about those who ‘go big’ is that they have senior executives who see digital technologies as strategic and transformative; they give sustained support and resources for long-term organisational change using disruptive technologies; and they appoint credible influential champions to make this happen. Technologies, including automation, are seen not as tools but as forming a digital platform for new business models, innovation, lines of business and relationships with customers. Interestingly, they rely on ‘big bets’ thinking, fuelled by a big picture view as to what the business needs and the technology can enable, and have less time for cost-benefit and total cost of ownership analyses. By contrast, those ‘hunkering down’ tend to be much more driven by such carefully calculated business cases, and have a much more bottom-up approach to utilising automation technologies for business value. There needed to be a much more convincing way to assess the value available for all parties.

This led us to ask the further question: “How can we get senior executives to understand the massive potential value that is there, and how to grasp it?” That led us on to develop our Total Value of Ownership Framework, shown in Figure 2, but detailed fully in our book Becoming Strategic With Robotic Process Automation (2019, SB Publishing) and in several articles.

Conclusion

If you wish to follow up on our research, please see below details of our research base as currently constructed—it is expanding all the time—and also details of relevant papers and books. You can find the articles downloadable from our website www.roboticandcognitiveautomation.com and the books can be purchased direct from www.sbpublishing.org.

Our research draws upon a KCP/LSE proprietary database of 500 plus RPA and cognitive automation cases studies taken from multiple sectors and economies. These were studied over time (from 2015–2021), and included ‘leader’, ‘follower’, ‘laggard’ and ‘also ran’ users of the technologies. We gained additional insight from four annual surveys in this period and from reviewing over 350 award submissions covering innovatory and effective automation practices. Earlier findings appear in four books and in the Blue Prism series Keys To RPA Success and Just Add Imagination, and published articles in Sloan Management Review, Harvard Business Review, LSE Business Review, Forbes and MISQ Executive. Building on these foundations, in 2021 we researched an additional 15 advanced user organisations taken from the banking and finance, insurance, health, telecommunications, and utilities sectors in the USA, Europe and Asia Pacific. We used interviews, documents, and survey questionnaires. We also reviewed over 350 award submissions covering innovatory and effective automation practices. The objective was to gain further insight into the technologies used and the business value being planned for, and achieved.

Reference

Willcocks, L. and Lacity, M. (2016) Service Automation: Robots and The Future of Work (SB Publishing, Stratford-upon-Avon)

Lacity, M. and Willcocks, L. (2017). Robotic Process Automation and Risk Mitigation: The Definitive Guide. (SB Publishing, Stratford-upon-Avon)

Lacity, M. and Willcocks, L. (2018) Robotic Process and Cognitive Automation: The Next Phase. (SB Publishing, Stratford-upon-Avon)

Willcocks, L., Hindle, J. and Lacity, M. (2020) Becoming Strategic with Robotic Process Automation, (SB Publishing, Stratford-upon-Avon).