Mary Lacity and Leslie Willcocks in conversation with Gabe Piccoli, MISQ Executive Editor

The Editor in Chief of MISQ Executive is Professor Gabe Piccoli. In December 2020 he asked Mary (Lacity) and Leslie (Willcocks) to discuss their six-year research program, with the goal of consolidating what we know about Robotic Process Automation, Cognitive Automation and AI, and identifying the remaining challenges for those organisations seeking business value from their automation investments. The conversation ranged widely, and the full transcript has been published in the MISQ Executive in June 2021, volume20, number 2.

Over three months we take highlights from and update the discussion, with this Part 2 dealing with business value, risks and jobs; Part 3 management and emerging challenges; and last month, in part 1, the trio talked about technology …

Gabe Piccoli: So, we’ve talked about what these tools are, and their histories, and how they work, but how do enterprises actually get business value from them?

Mary Lacity: We, and others, have studied implementations with outcomes ranging from what we describe as a ‘triple-win of value’ to complete failures. We think it’s most useful to focus on the success stories because practitioners like to learn from and hopefully mimic the achievements of early adopters. But we also had to study failures so we could identify the action principles that differentiate outcomes.

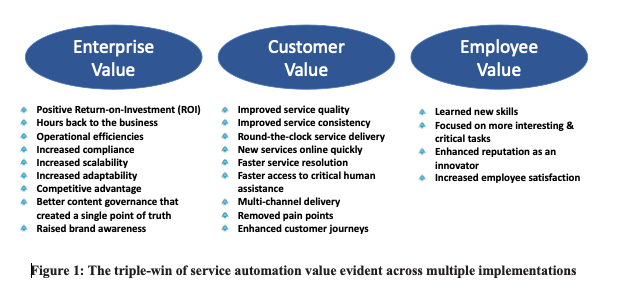

Let’s look at the successful implementations. Many of our case study organisations achieved the triple-win for three stakeholders: the enterprise, customers, and most surprising of all—employees. The Associated Press; BNY Mellon; Bouygues; Deakin University; Ericsson; EY Tax Advisory; KPMG; Mars; Nielsen Holdings; Nokia; nPower; SEC Bank; Shop Direct; Standard Bank; Telefónica O2; the VHA; Xchanging; and Zurich Insurance are examples of companies that achieved at least one source of value from each category. Aggregating these findings, we have listed the specific benefits and sources of enterprise, customer, and employee value that RPA and CA has delivered across case study companies (see Figure 1).

Gabe Piccoli: That list seems a little too good to be true. Can you provide some examples?

Leslie Willcocks: Our two papers in MISQE provide detailed examples. Keep in mind we studied manifest successes initially, to see if there was any ‘there’ there! The Telefónica O2 paper discussed the value to the company in terms of cost savings, the value to customers who received faster services, and the value to internal employees, who were released from dreary work to focus on more interesting tasks. The Deakin University paper detailed the triple-win of value for three stakeholders: the university raised their global brand awareness, students gained faster access to critical services, and staff focused on more interesting tasks. The evidence from other companies is in several other studies, including our own.

Gabe Piccoli: What do failures look like? What were some of the key missteps leaders made early on?

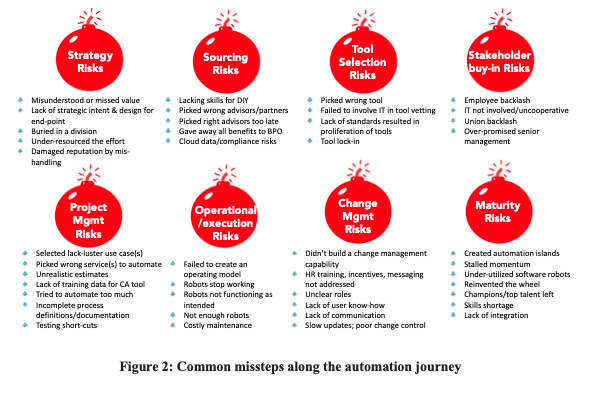

Mary Lacity: We purposefully started researching failures for our second book, Robotic Process Automation and Risk Mitigation: The Definitive Guide. It’s always hard to find companies willing to talk about their blunders, though there are quite a few accounts of the limitations as well as the benefits of the automation we are describing. The software providers and consulting firms we were working with at the time—including Alsbridge (now part of ISG), Blue Prism, Everest Group, HfS, ISG, and KPMG—helped us identify failure cases. We studied many enterprises that failed to deliver value, resulting in such outcomes as employee sabotage because of mishandled human resource (HR) policies; automations that soon failed functionally due to poor change management; and automations that irritated, rather than delighted, customers. Additionally, some organisations had localised successes with a few projects, but they never succeeded in scaling and maturing the capability across the enterprise.

We identified over 40 risks—which you can consider to be missteps—in the areas of strategy formulation, sourcing, tool selection, stakeholder-buy-in, project management, operations, change management, and maturity risks (see Figure 2).

Gabe Piccoli: Well, that is quite sobering. Which practices are responsible for differentiated outcomes? What is the pattern of practices that are unique to this technology? I am sure some the classic practices leading to successful project completion apply (e.g., top management support). But which are the unique practices you found to be critical to success for RPA/CA?

Leslie Willcocks: Overall, we identified over 30 action principles that were associated with good outcomes. You are right, Gabe, one of our first stakeholder lessons is in fact, ‘Gain C-suite support to legitimate, support, and provide adequate resources for the service automation initiative.’ Many of our action principles are commonly known to apply to any type of organisational adoption, such as getting stakeholder buy-in and following Pareto’s rule by automating the smallest percentage of tasks that account for the greatest volume of transactions. We do see value in replicating known practices—they reaffirm what managers already know about successful technology implementations. Managers need to retain many of their practices in the face of a new technology. But we did reveal provocative findings and new insights.

Many people, for example, falsely assume the ROI from automation comes from firing employees. While it’s true that service automation’s primary source of enterprise value is freeing up human labour, the best way to deliver, measure and communicate this value to the enterprise is ‘hours back to the business’. You can think of it as a gift given back to the organisation. What will an organisation do with that gift? Most enterprises we studied used excess labour capacity to redeploy humans to other tasks within the work unit. Many of these organisations were in high growth mode, and automation helped them take on more work without hiring proportionally more workers.

Gabe Piccoli: Can you explain how ‘hours back to the business’ is different than what we normally think of in terms of freeing up full-time equivalents (FTEs)?

Mary Lacity: They are commensurate, but the messaging is very different. ‘Hours back to the business’ calculations are based on estimating the number of hours it would have taken if humans still performed the tasks. It represents the human capacity that is now free to do different work. Hours back to the business can be converted to FTEs, typically by dividing the number by 2,000 hours, the average number of hours an employee works per year. So, for example, EY’s US Tax Advisory Business generated 800,000 hours back to the business within 18 months of its RPA implementation. If EY would have reported that automation saved them 400 FTEs instead of the equivalent 800,000 hours, someone in management might assume and employees might fear, “We no longer need 400 people”. But that sends the wrong message, as the labour savings typically come from automating a portion of people’s jobs. For example, 400 FTE savings is more likely coming from automating 20 percent of 2,000 people’s jobs.

Gabe Piccoli: : Surely some automation implementations lead to layoffs.

Leslie Willcocks: Well, that’s where it gets interesting! Firstly, we are talking here of time saved that can be used elsewhere in the organisation. Secondly, the time saving is invariably spread across jobs. It’s partial task automation, not job loss. Thirdly, people fail to understand that there is an enormous amount of extra work being generated every year in organisations—in one study we suggest between 8-12 percent. This arises from the exponential data explosion, increasing audit, regulation and bureaucracy, and the problems information and communications technologies bring with them—look at cybersecurity as an obvious example. Rising workloads allied to skills shortages have pressured organisations to turn to automation as a coping mechanism, rather than primarily for headcount reduction. The results some have been getting are shown in Figure 1.

But Gabe, you are correct, but layoffs have not been as widespread as one might think, especially during the time frame that we studied from 2015–2020. That has been a common finding across several major surveys. Davenport and Rananki, (2018) found that, for RPA, replacing administrative employees was neither a primary objective nor a common outcome. Only 22 percent of executives thought headcount reduction the primary objective with AI. KPMG/HFS (2019) found that for those employees displaced by AI, 14 percent would be let go, the rest retrained. On a bigger frame, Manyinka and Bughin, (2018) saw three simultaneous ‘AI’ impacts: jobs lost, jobs gained, jobs changed. On their mid-point scenario, jobs lost by 2030 could displace 400 million workers but would be outweighed by 555-890 million jobs gained, while many more jobs would be changed by automation than would be lost.

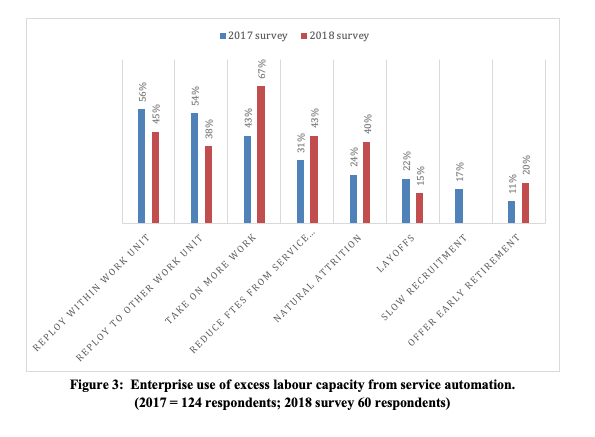

Mary Lacity: I think it’s worth sharing the findings from surveys we conducted with our colleagues John Hindle and Shaji Khan. We collected two surveys—one in 2017 (of 124 senior managers) and one in 2018 (of 60 service automation adopters). We asked respondents, “What does your organisation do with the labour savings generated from automation?” Only 22 percent of the respondents in the 2017 survey and 15 percent of the respondents in the 2018 survey indicated that their organisations laid off employees as a consequence of automation (see Figure 3). Other enterprises did reduce headcount, but not through lay-offs. Instead, they took a gentler approach to ratcheting down headcount gradually by waiting for natural attrition, slowing recruitment, or offering early retirement.

For that two-year period, our research found that service automation technologies were most commonly used to free up employees from dreary, repetitive work so that employees can focus on more value-added tasks. Specifically, most enterprises used excess labour capacity to redeploy humans to other tasks within the work unit or to other work units within the company, for example to reduce the backlog of work and to take on more work without adding more headcount. This was particularly evident in shared service organisations that were under pressure to take over more services without adding more employees. A lot were channelling employees into more customer facing roles and also combining tasks to redefine what constituted a ‘job’.

Thirty-one percent of the respondents in the 2017 survey and 43 percent of the respondents in the 2018 survey reduced reliance on their service providers. The major ITO and BPO providers were well aware that their labour arbitrage business model was severely under threat by automation—they feared losing long-time customers who needed fewer services from outsiders after automation. MISQE published a case study on how one provider, OpusCapita, made the strategic decision to build up a significant RPA capability internally, and then extended RPA services to customers. Many other ITO and BPO providers followed suit.

Gabe Piccoli: Share some more surprises from your research.

Leslie Willcocks: Before our field research, we had assumed employees would be threatened by automation. Instead, we found that the employees who embraced automation developed highly valued skills, and many of them were either promoted within their organizations or went on to join or start consulting companies. Over the course of six years, the employees we interviewed went on to have amazing careers.

Mary Lacity: The lesson is that human resources (HR) needs to be involved in intelligent automation if enterprises want to retain their talent. They need new job descriptions, better compensation packages, and opportunities to grow. This is going to be particularly pertinent following the COVID19 crisis. Another lesson relevant to HR is that they may need to redesign employee scorecards after automation. If they don’t, an individual employee’s productivity metric might decline after automation because the employee will focus on more complex work as the robots take over the easy tasks. For example, in one case study on healthcare claims processing, the average human productivity was 12 claims per hour before automation. After automation, human productivity fell to about seven claims per hour because they only worked on claims too complex for the automation tool. The employees were obviously unhappy. The healthcare company needed to adjust expectations and compensation to recognise the more complex work.

… To Be Continued – Part 3 is published in July 2022

Citations

i. See Asatiani, A. and Penttinen, E. “Turning robotic process automation into commercial success – Case OpusCapita,” Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases (6), 2016, pp. 67-74; Davenport, T. and Kirby, J. (2017) How Smart Are Smart Machines? MIT Sloan Management Review, 57, 3, 21-25; Hallikainen, P. Bekkhus, R. and Pan, S. (2018). Lacity, M., Willcocks, L. and Craig, A. (2015). “Robotic Process Automation at Telefónica O2,” The Outsourcing Unit Working Paper Series, Paper 15/02, London School of Economics; Lacity, M. and Willcocks, L., (2016) “A New Approach to Automating Services,” MIT Sloan Management Review (58:1) pp. 40-49; Lowes,P. and Cannata, F. Automate this: The business leader’s guide to robotic and intelligent automation, Deloitte, 2017; Schatsky, D., Muraskin, C. and Iyengar, K. Robotic process automation: A path to the cognitive enterprise, Deloitte University Press, 2016; Watson, H. (2017). Preparing For The Cognitive Generation of Decision Support, MISQ Executive, 16, 3, 153-169; Willcocks, l., Hindle, J. and Lacity, M. (2019) Becoming Strategic With Robotic Process Automation. SB Publishing, Stratford.

ii. As examples only: Davenport, T. (2018). The AI Advantage: How to put the artificial intelligence revolution to work. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass; Smith, R. E. (2019) Rage Inside The Machine. Bloomsbury Press, London; Broussard, M. (2018) Artificial Unintelligence. MIT Press, Boston; Smith, G. (2018) The AI Delusion. Oxford University Press, Oxford; Russell, S. (2019 Human Compatible. Allen Lane, UK

iii. See Willcocks, L. (2020). Robo-Apocalypse Cancelled? Reframing the automation and future of work debate. Journal of Information Technology, 35, 4, pp.286-302. Also Willcocks, L. (2021) Robo-Apocalypse? Response and Outlook on the Post- COVID-19 Future of Work. Journal of Information Technology (forthcoming).

iv. KPMG/HFS Research (2019) Easing The Pressure: The State of Intelligent Automation. KPMG,April. The rest would be retrained in data, on AI-related tasks, on a specific process or industry domain, or to service new business needs

v. See Davenport, T. and Rananki, R. (2018) Artificial Intelligence for The Real World. Harvard Business Review, January-February; Also Manyinka and Burghin, (2018). The Promise and The Challenge of The Age of Artificial Intelligence, McKinsey Global Institute, Executive Briefing, October.

vi. Hallikainen, Petri; Bekkhus, Riitta; and Pan, Shan (2018) "How OpusCapita Used Internal RPA Capabilities to Offer Services to Clients," MIS Quarterly Executive: Vol. 17 : Iss. 1 , Article 4.Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol17/iss1/4; Asatiani, A. and Penttinen, E. “Turning robotic process automation into commercial success – Case OpusCapita,” Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases (6), 2016, pp. 67-74.