Mary Lacity and Leslie Willcocks in conversation with Gabe Piccoli, MISQ Executive Editor

The Editor in Chief of MISQ Executive is Professor Gabe Piccoli. In December 2020 he asked Mary (Lacity) and Leslie (Willcocks) to discuss their six-year research program, with the goal of consolidating what we know about Robotic Process Automation, Cognitive Automation and AI, and identifying the remaining challenges for those organisations seeking business value from their automation investments. The conversation ranged widely, and the full transcript has been published in the MISQ Executive in June 2021, volume20, number 2.

Over the past two months we have taken highlights from the discussion. This, Part 3, is the final paper focuses on management and emerging challenges.

Gabe Piccoli: What are the key recommendations on intelligent automation that you give to companies when you do consulting with firms starting or progressing an RPA/CA journey?

Leslie Willcocks: For those just starting their journeys, Mary summarised the action principles with this advice: think big, start small, institutionalise fast, and innovate continually. By thinking big, we mean that enterprises need to develop an intelligent automation capability to thrive in the 21st century. They need to think strategically about automation from the start by focusing on the triple-win of value that is possible for the enterprise, its customers and employees. They can start small with a pilot, but they likely do not need to do a proof of concept; the technology has already been proven, particularly for RPA. A pilot includes a business sponsor, IT security, IT operations, compliance teams, and HR so that the automation will be designed for production from the start. There are also plenty of competent advisory firms that can help. Institutionalise fast refers to creating an organisational structure and change management capability to mature and scale intelligent automation throughout the enterprise. Many companies set up a Centre of Excellence. Finally, automations need to be managed and continually improved…software robots are more like digital employees who need retraining when business rules change and who can improve proficiency with more feedback.

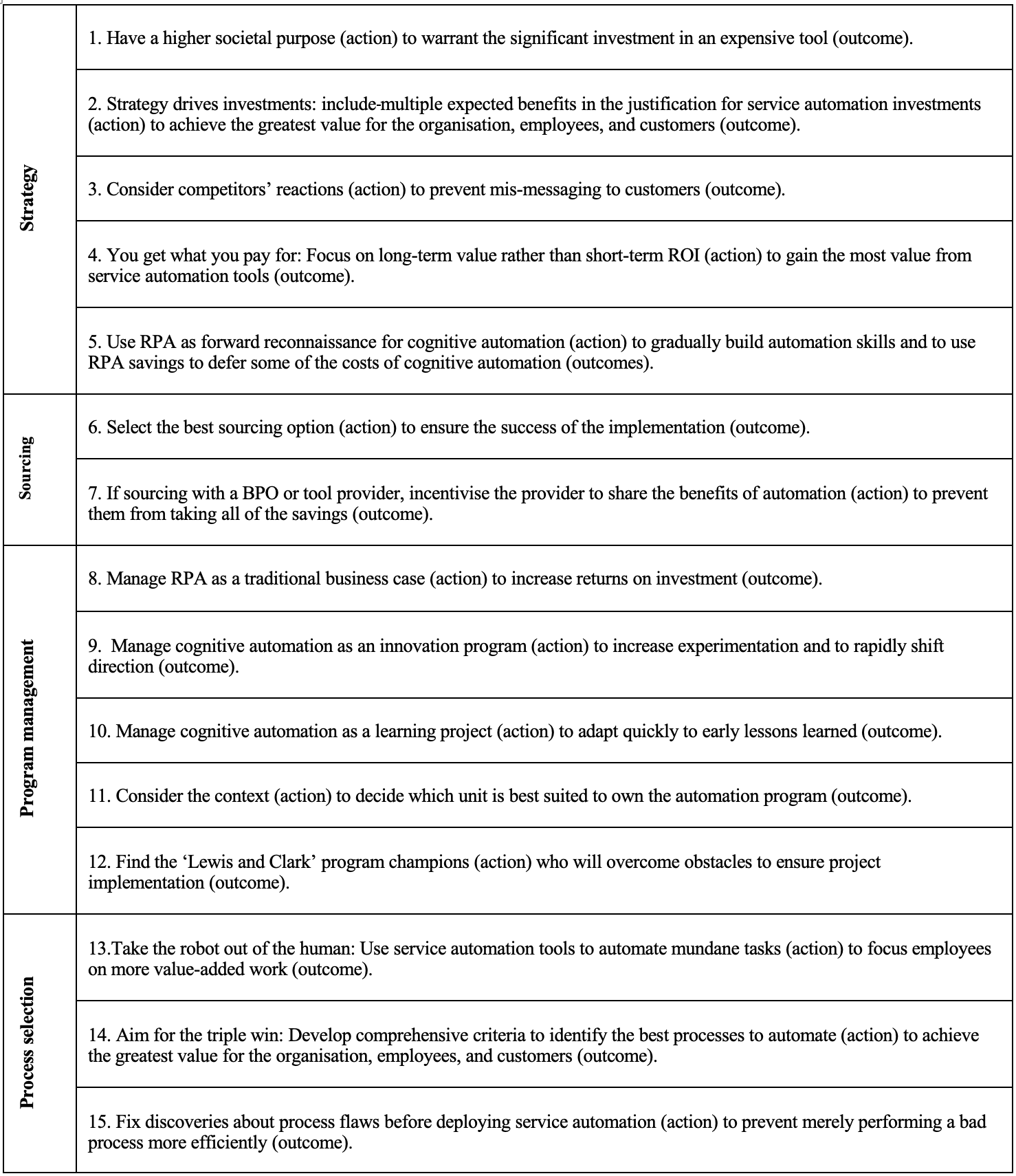

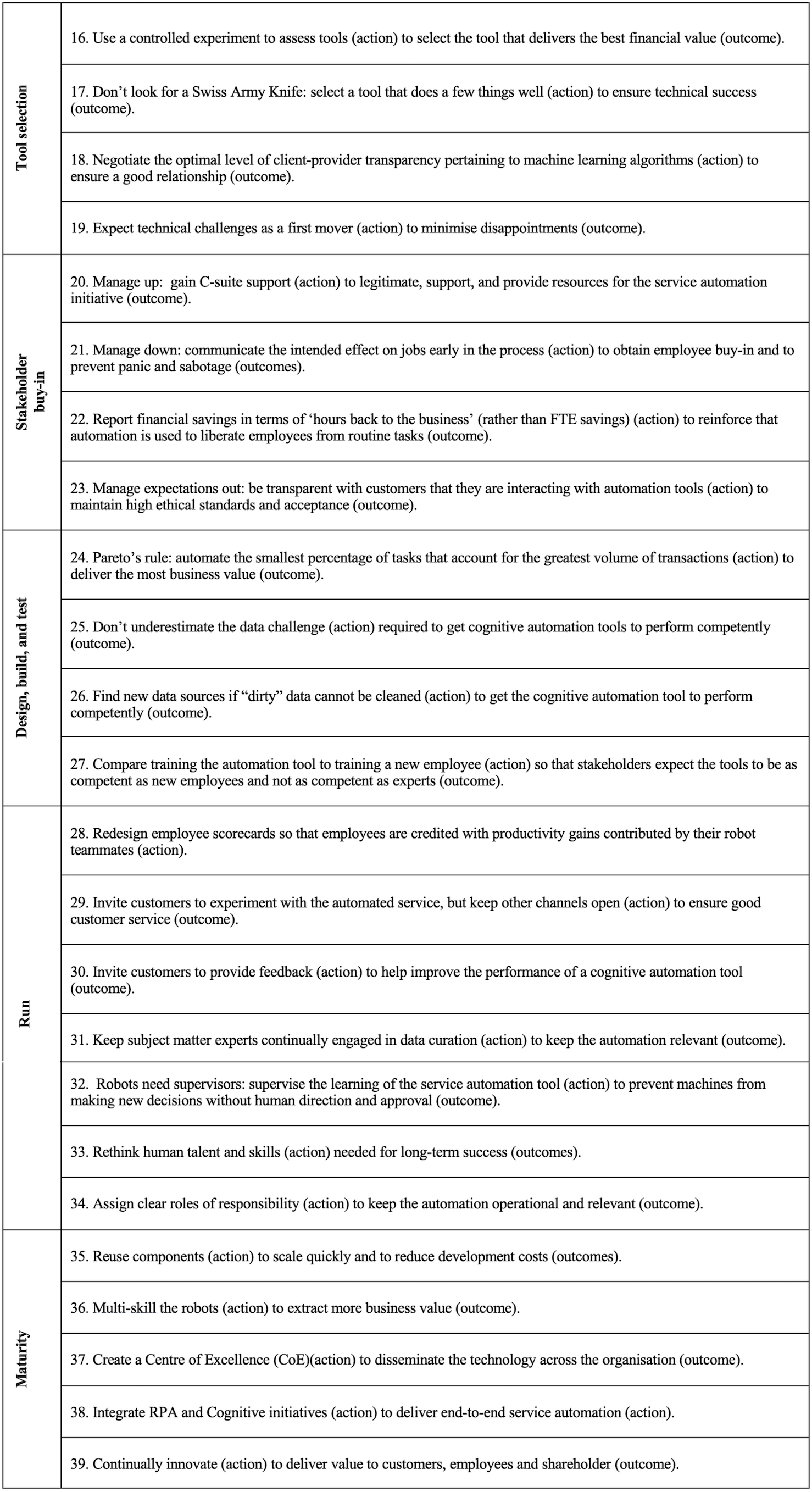

Mary Lacity: As far as progressing an RPA/CA journey, we have done now, by mid 2022, some eight years research on this and our summary is shown below. Action principles are practices identified by our research that produced desirable results in real world automation implementations. Action principles are grounded in data and are designed to assist other thoughtful agents as they embark on their own implementation journeys. Action principles are similar to best practices in that both seek to share knowledge from prior experiences. But whereas ‘best practices’ imply that mimicry is always recommended and will always produce similar results, action principles recognise that context matters. The usefulness of a practice depends on the objectives the organisation is trying to achieve, whether the organisation has the absorptive capacity to implement the practice effectively; and timing—there are better times than others to apply a specific practice. We leave it to the thoughtful managers to assess the applicability of the action principles to their contexts.

Let me call out a few of the Action principles here. Particularly for cognitive automation (CA) deployments on customer-facing services, initial performance will not be perfect because, as we mentioned, CA tools produce probabilistic outcomes rather than deterministic outcomes. No matter how much organisations tested the tool in their sandbox environments, they never predicted how customers would actually interact with the technology after it went live. SEB Bank learned to warn customers that a virtual software assistant would take the first attempt at answering their query and gave customers quick access to a human if customers got frustrated. At SEB Bank, IPsoft’s Amelia initially handled about 50 percent of text chat conversations without needing human intervention. By continually analysing the live customer interactions, SEB Bank updated the tool to perform better over time.

Multi-skilling the robots is an example of a unique RPA practice. Initially, many organisations were buying one software license, i.e., one software robot, per automation process. Several robots would be idle during different times of the workday. While a human workforce tends to have specialist skills that cannot be dynamically re-routed to balance out demand fluctuations from across the enterprise, and while humans require rest, a software robot can be programmed to run different tasks and operate 24 hours a day. It took a while before organisations realised that they could program a single software robot to automate several processes, provided they scheduled them at different times. The RPA providers do not like that insight because it results in the purchase of fewer software licenses.

Leslie Willcocks: If I can add… by now the smart organisations are looking to integrate automation into a much bigger digital transformation, and RPA and CA are actually fundamental to such transformations, not a useful ‘quick-win’ appendage. But then automation becomes even more difficult, because digital transformation is a large-scale, long-term, complex process in any long-standing organisation of size.

Gabe Piccoli:: What are people struggling with these days? What challenges should authors work to ‘solve’ for IT leaders in this space at this time?

Mary Lacity: Here, we’ve only focused on two automation enabling-technologies, RPA and CA. The first-generation intelligent automation tools we’ve discussed are adopted within the boundaries of the firm, but the next phase of intelligent automation is happening in cooperation with ecosystem partners. Gabe, we know you are working on a project with Barb Wixom at MIT CISR on inter-organisational data sharing—that is a great example of the next generation of competitive advantage. These are ecosystem-level solutions.

On our part, we are studying how blockchains help automate interorganisational transactions. In our case studies, algorithms and technologies were between 20 and 30 percent of the effort required to create a successful blockchain application. Up to eighty percent of the effort requires trading partners to agree on data and event standards, shared governance models, intellectual property rights, and compliance assurance. There’s a lot more to learn.

Leslie Willcocks: Yes, meanwhile looking at automation, we have identified a number of areas where managers and organisations really need help. The first is that they struggle to scale their automation. By the end of 2019, only 13 percent had scaled and industrialised their RPA deployment and only 12 percent had an enterprise approach to automation. We looked at this again in late 2020, and while the top vendors had lots of customers, very few of those customers had more than 100 software robots. We think some of this is because the cost of getting to the next stage looks steep, though we have evidence to suggest that the benefits can be exponential. There are also problems technologically of integrating with existing or new IT, let alone across the enterprise. The C-suite tends not to see these technologies as strategic, are too remote from the programs, and frequently under-invest in automation. We are sure there are other reasons that deserve research.

If RPA deployment has problems, then cognitive automation technologies have a lot more—which are well worth researching from a practice-based perspective. If you listen to too much AI hype, it’s very easy to underestimate how slow and challenging progress has been to date. On cognitive, to summarise these, we developed an acronym BOGSHABIB standing for brittle; opaque; greedy; shallow; hackable; amoral; biased; invasive; and blurring (fakeable). It’s a pretty rich list of things that practitioners need help with.

How to integrate automation into digital transformation programmes? Interestingly our research into 2022 has seen banks and telecom companies driving digital transformation and automation efforts from different places, with different executives. As a result, RPA/CA can get becalmed and slow progress on digital transformation can hold up integrating the automation agenda.

There has been little research on ‘born digital’ companies and how they use automation technologies. Does that exhibit different usages and perhaps more strategic deployments? Finally, lots of studies now show that the pandemic and economic crises have accelerated the deployment of automation, but so far we have found they have been used differently—to sweat assets, or underpin current business performance, or the crisis might have slowed the automation strategy. Only a few organisations are really investing strategically—it may be as little as 20 percent. But this deserves much more study going forward as we are sure the picture will change dramatically over the next three years.

Citations

i. Wade, Michael and Shan, Jialu (2020) "Covid-19 Has Accelerated Digital Transformation, but May Have Made it Harder Not Easier," MIS Quarterly Executive: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol19/iss3/7

ii. See Willcocks, L. (2021) Global Business: Management. SB Publishing, Stratford-upon-Avon. Available from info@sbpublishing.org