Leslie Willcocks and Mary Lacity

Using software to automate tasks is not a new idea, but interest in service automation has certainly escalated in recent years. Provocative titles like ‘Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future’ (Ford 2015), ‘A World without Work’ (Thompson 2015), ‘Rise of the Robots: How long do we have until they take our jobs?’ (Devlin 2015) and ‘The Globotics Upheaval’ (Baldwin, 2019) fill the popular press. Although the term ‘robot’ conjures images of physical robots wandering around offices, the term as it relates to service automation really means the delivery by software of service tasks previously performed by humans. With Mary Lacity, and subsequently with John Hindle and Daniel Gozman, I have been studying early organisational adopters of service automation technologies since 2014 through to the present day. In this first article I would like to take you on the journey we have been on, as it is very much the journey of automation itself as applied in developed economies. It will also give you insight into why we are convinced by our findings. I will also identify the first 13 management actions that were leading to effective automation deployments.Making Sense of the Robo-Babble

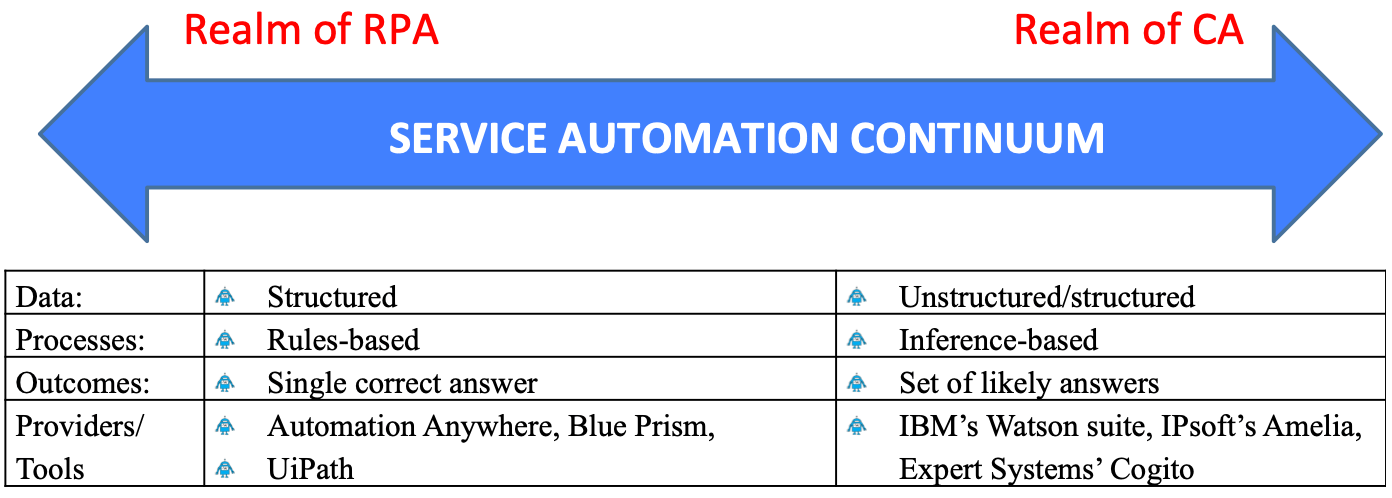

At the beginning of our research, we were bombarded by the proliferation of technical jargon, with names such as macros; scripting tools; robotic process automation (RPA); cognitive intelligence; machine intelligence; artificial intelligence; virtual agents; intelligence amplification; automatic content generators; cognitive learning technologies; autonomic platforms; cognitive computing; and business process management (BPM) systems, as some common examples. You have probably experienced the same level of bewilderment as we did. Our first response was to create a simple service automation continuum. It will assist you, as a reader, if I introduce it now ...

We asked a very straightforward question to make sense of the proliferation of service automation jargon: What types of tasks are the tools designed to automate or augment? Looking at the data, process, and outcomes, we conceived of service automation comprising a continuum (see Figure 1). Anchored on one side is the realm of RPA; the other, Cognitive Automation (CA). (We do not call CA technologies ‘Artificial Intelligence’ because the ‘AI’ label aggrandises what these tools, do in our opinion—I have discussed this in previous blogs.

The realm of robotic process automation (RPA) consists of tools that aim to automate tasks that have clearly defined rules to process structured data to produce deterministic outcomes. So what’s new here? A software ‘robot’ is configured to do computer tasks the way humans do, by giving it a logon ID, password, and playbook for executing processes. For example, an RPA tool can perform a credit check needed by an internal ERP system by logging on to a credit bureau website, entering the search terms, and recording results back to the ERP system. RPA has two distinctive features compared to other automation tools like BPM solutions and Software Development Kits (SDKs). First, RPA is easy to configure with drag-and-drop process design, so developers don’t need programming skills, just process and subject matter expertise. Second, RPA software is non-invasive because it accesses other systems through the presentation layer—no underlying systems are touched. Automation Anywhere, Blue Prism, and UiPath were the top RPA tools by market share as of 2019. And they continue into 2023 to be the top specialised automation suppliers.

The realm of cognitive automation (CA) consists of tools that aim to automate or augment tasks that do not have clearly defined rules. With CA technologies, inference-based algorithms process data to produce probabilistic outcomes. The data is often unstructured, such as natural language, either written or spoken. For example, a CA tool may be used as a first-responder dispatcher to categorise a customer request. The tool will be instructed to route the request only if a certain confidence threshold has been met, such as the tool is ninety percent confident the call pertains to a new mortgage application. The data can also be highly structured, such as the pixels in an image. Whether the data is unstructured to structured, CA tools require a significant amount of training data. For example, Andrew Ng (2016), Founder of Google’s Brain Deep Learning Project, wrote that it takes tens of thousands of labelled pictures to recognise people. Some of these tools also claim to have emotional intelligence capabilities, the ability to assess another human being’s sentiment or state of arousal. CA tools require a significant amount of data analytics, business process, and IT skills to train them to proficiency. IBM’s Watson suite, Google’s Machine Learning Kit, IPsoft’s Amelia, and Expert Systems’ Cogito are examples of CA tools. /p>

Given the newness of these service automation technologies, there are many unanswered questions. We conducted empirical research to answer two high-level questions:

- 1. Why are clients adopting service automation and what outcomes are they achieving?

- 2. What practices distinguish service automation outcomes?

Our research results have been published in numerous books, practitioner journals, white papers, and working papers. My purpose here is to provide an example of our research-into-practice method. We show how the process of inquiry produces what we call ‘action principles’. Action principles are practices that explain the results found in real-world implementations. Action principles are co-created with practitioners. They are lessons learned from practices enacted in the contexts studied. To illustrate the method, we first share why we became interested in the topic of service automation. Then we describe our data collection methods and how the action principles, which are both rigorous and relevant, arose from these methods.

Topic Selection: ‘Is there any there there’?

In late 2014, we were just completing a four-year research project on business process outsourcing (BPO), when the consulting firm HfS starting talking about robotic process automation (RPA) as a new breed of tools designed to automate back office services (HfS Research 2014). Practitioners were also talking about IBM’s Watson use in healthcare , and a plethora of other new tools designed to assist or replace human knowledge workers. Our curiosity was piqued, but we were not convinced that ‘there was any there there’—to paraphrase Gertrude Stein. To investigate, my co-author Mary Lacity went to the launch of the Institute for Robotic Process Automation (IRPA) in New York City in late 2014. She met some early client adopters of RPA, including A.J. Hanna of Ascension Shared Services and Lou Ferrara of the Associated Press. Ascension was using RPA to update HR records and to process payments. The Associated Press was making headlines for using a tool to generate news stories. She also met RPA tool providers, including Pat Geary, the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) of Blue Prism. After that event, we decided to devote our time to study the space. There was no academic literature to search because none existed. Instead, we entered a messy world of provider hype ... with no compass.

Planning Field Work

After the IRPA event in 2014, we formulated our research plan. We needed key participants at the front lines of service automation adoption to answer the research questions. Key participant interviews were an appropriate method because we sought answers to questions in which the subject matter was sensitive (like any form of automation) and because we were more concerned with the quality, not quantity, of responses. We planned to start our interviews with a very simple request: ‘Tell us your automation story from your perspective’. To fill in gaps in participants’ narratives, we intended to prompt them to discuss their service automation adoption journey in detail, including the aims of the automation, the practices enacted, outcomes, and lessons learned. The specific questions planned were:

- • Client adoption journey: Why was automation considered? What was your initial business case? Who was involved? Did you do a proof-of-concept, and if so, when and on what process? How was the process selected? What tool did you pick and why? How did you manage the implementation?

- • Business value delivered. How has service automation delivered on the initial business case in terms of financial (i.e., cost savings, return on investment (ROI), operational (i.e., improved quality, faster delivery, better compliance), and strategic value (i.e., strategy enablement, access to new customers, better customer retention)?

- • Lessons learned: What overall lessons did you learn? If you had to do your service automation implementation all over again, what three things would you change, and why?

We also planned to interview the service automation providers at each client site, as well as any advisory firms that assisted with the client’s adoption journey.

Field Research Begins

Beginning in January 2015, we started formally interviewing contacts made through the IRPA. Ascension Shared Services and the Associated Press were the first case studies, both based in the United States (US). Immediately, our interviews were yielding surprising findings. Neither organisation used RPA to fire employees as suggested by the popular press. Instead, the RPA tools were performing mundane tasks so that employees could focus on more value-added work. A journalist, it turns out, would rather interview a CEO than write a corporate earnings report. An accounts payable associate would rather reconcile records than copy and paste fields from a spreadsheet into an ERP system. Both organisations were under pressure to do more work without adding more headcount, and RPA was a way to achieve it.

Meanwhile, the CMO of Blue Prism provided introductions to the next two case studies at Telefónica O2 and Xchanging in the United Kingdom (UK). Based on just four cases, we were beginning to see patterns across the cases. So far, none of the four companies laid off employees as a consequence of automation and all reported multiple business benefits besides just cost savings. Interesting differences arose as well: the business sponsors at Ascension and Telefónica O2 excluded the IT department whereas the business sponsors at the Associated Press and Xchanging included IT. There were also unique practices. For example, employees at Xchanging embraced RPA to the point where they anthropomorphised their software robots by giving them names, depicting them, inviting them to office parties, and holding contests for the ‘coolest robot’.

For each case, we (as researchers) flush out the action principles in the form of lessons learned, and review these with interviewees until we reach a common understanding. Thus, action principles are co-produced among researchers and participants.

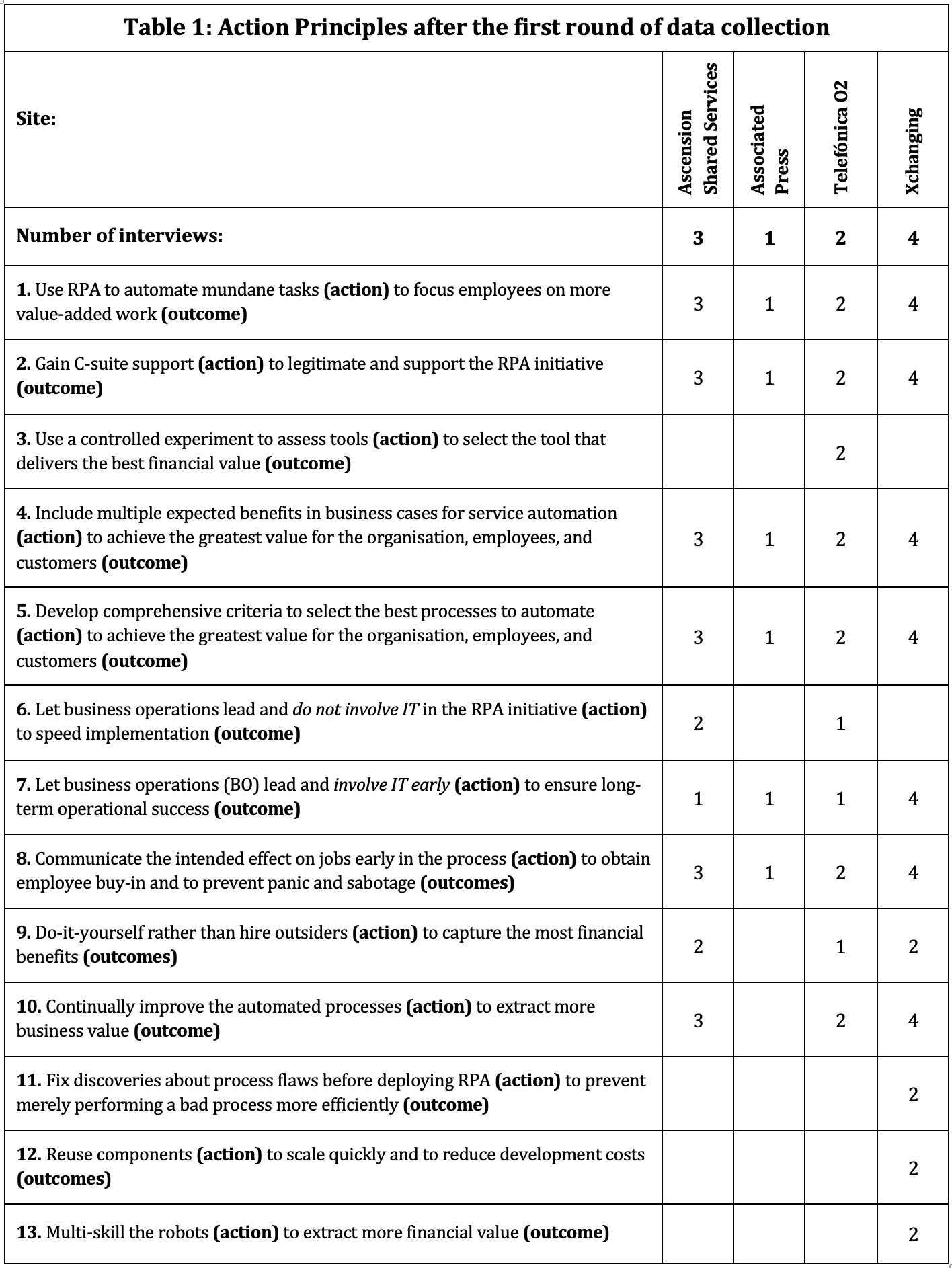

We typically generate between five to ten action principles at each organisation, sometimes based on a single interview with a key participant. For example, we initially identified the following action principles for the Telefónica O2 case:

- 1. Test RPA capabilities with a controlled experiment by asking multiple RPA tool providers to compete on an identical proof-of-concept.

- 2. Develop criteria for determining which processes can be automated from a business and technical perspective.

- 3. Let business operations lead.

- 4. Include multiple expected benefits in business cases for service automation.

- 5. Communicate the intended effect on jobs early in the process.

- 6. Do-it-yourself (Telefónica O2 insourced automation at the time because there were no consultants specialising in RPA back in 2010 when it first adopted RPA.)

- 7. Continually improve the automated processes

With each subsequent case, we built a matrix of action principles across contexts. Table 1 provides an early version of the action principles extracted from the first four adoption journeys. (The table comes from Lacity, Willcocks and Gozman, 2021. This paper provides a very detailed account of all our finidngs). You will note that Telefónica O2’s lesson ‘let business operations lead’ has evolved to ‘let business operations lead, but bring IT onboard early.’ Participants from Telefónica O2 and Ascension Shared Services finally reversed their decisions not to include IT. The business sponsor at Telefónica O2 who implemented RPA without informing the CIO was nearly fired for giving the software robots his personal ID and password. Ascension’s service automation projects were scaling so fast, they needed IT’s input.

Conclusion

We had reached an interesting stage in the research. There had been many surprises. Many myths found in the popular literature had been contradicted. Managers were not automating to cut headcount but because they had labour shortages, productivity problems, and were dealing with ever rising workloads. Most employees did not resist the technology; many embraced it as an opportunity—for example, to get rid of low grade tasks, to gain new skills, to be involved in innovation, or to get more work done. RPA was not being used particularly to bring back previously offshored jobs. Not all tools called RPA were the same. Not all processes could be automated effectively. RPA did NOT mean that a business manager could automate without reference to the IT department and IT specialists. There were many other discoveries. And by this point we also had a good 13 principles we could recommend to practitioners.

By December 2022 we had assembled a case database of over 1100 applications of RPA, CA and other digital technologies. Using various analytical techniques and benchmarking frameworks we can now provide rich assessment and advice to organisations on not just their automation efforts, but also their digital transformation strategies and progress. But this is to get ahead of ourselves.

In the next article I will describe how we began to build a bigger and richer database and eventually added another 26 to those 13 automation management principles.

References

Lacity, M. Willcocks, L. & Gozman, D. (2021). Influencing information systems practice: The action principles approach applied to robotic process and cognitive automation. Journal Of Information Technology, 36, 3, 216-240.

For a comprehensive management approach to automation see:

Willcocks, L., Hindle, J. & Lacity, M. (2019) Becoming Strategic With Robotic Process Automation. SB Publishing: Stratford-upon-Avon, UK.

Foot notes

- 1 ‘WellPoint and IBM Announce Agreement to Put Watson to Work in Health Care,’ Press release, 09/12/2011; ‘In year two, MD Anderson Moon Shots Program begins to spin off innovation,’ MD Anderson News Release 10/30/14; ‘Memorial Sloan Kettering Trains IBM Watson to Help Doctors Make Better Cancer Treatment Choices,’ April 11 2014; ‘Cleveland Clinic uses IBM's Watson in the cloud to fight cancer.’ Computerworld UK, 10/29/2014.