Leslie Willcocks & Mary Lacity

In the first two papers (Parts 1 & 2), I documented our initial findings on effective action principles, the major risks experienced in automation programs, and how to mitigate these risks. But we did not stop there, because we know that emerging technologies is a very rich, mostly unexplored area and that ever new findings emerge as organisations adopted robotic process automation and cognitive automation. During 2018 we researched cognitive automation a lot more and found enough cases and evidence to update our findings on RPA action principles, and also to cover cognitive technologies. By then we had enough confidence in our data to publish a book of our complete findings to date: Robotic Process and Cognitive Automation—The Next Phase.

Thereafter we built our case database even further, brought on board as co-researcher Dr John Hindle from Knowledge Capital Partners, and by 2019/2020 had extended the database to over 500 cases. The essence of our findings was distilled in our book Becoming Strategic With Robotic Process Automation. By the end of 2022 the research base exceeded 1,100 cases, and included cases of RPA, cognitive automation, intelligent automation and digital transformation. Our ongoing research will lead to further books on optimising the value of automation and on globalisation automation and work.

But the purpose of the present article is to highlight out robust findings on management action principles for automation.

Distilling Further Action Principles

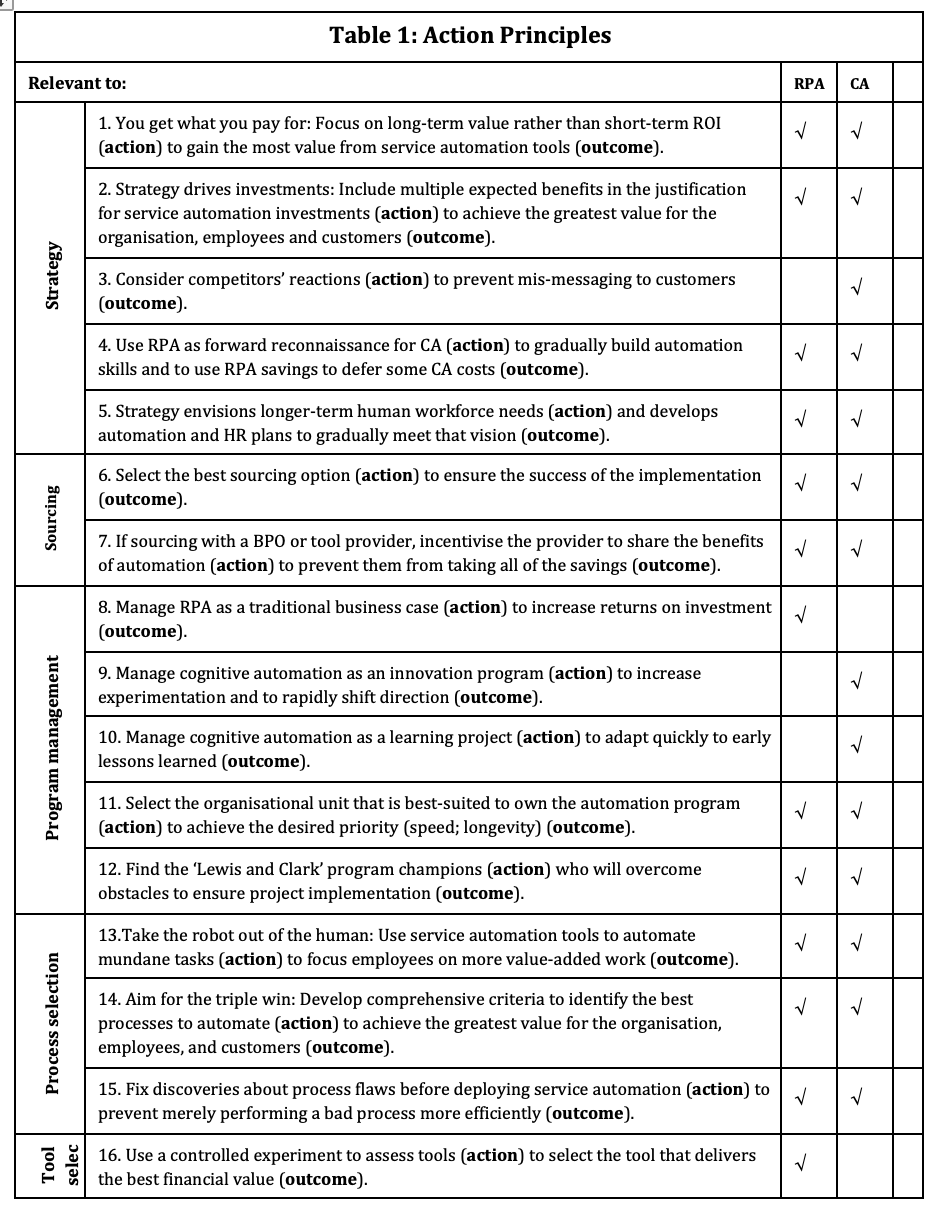

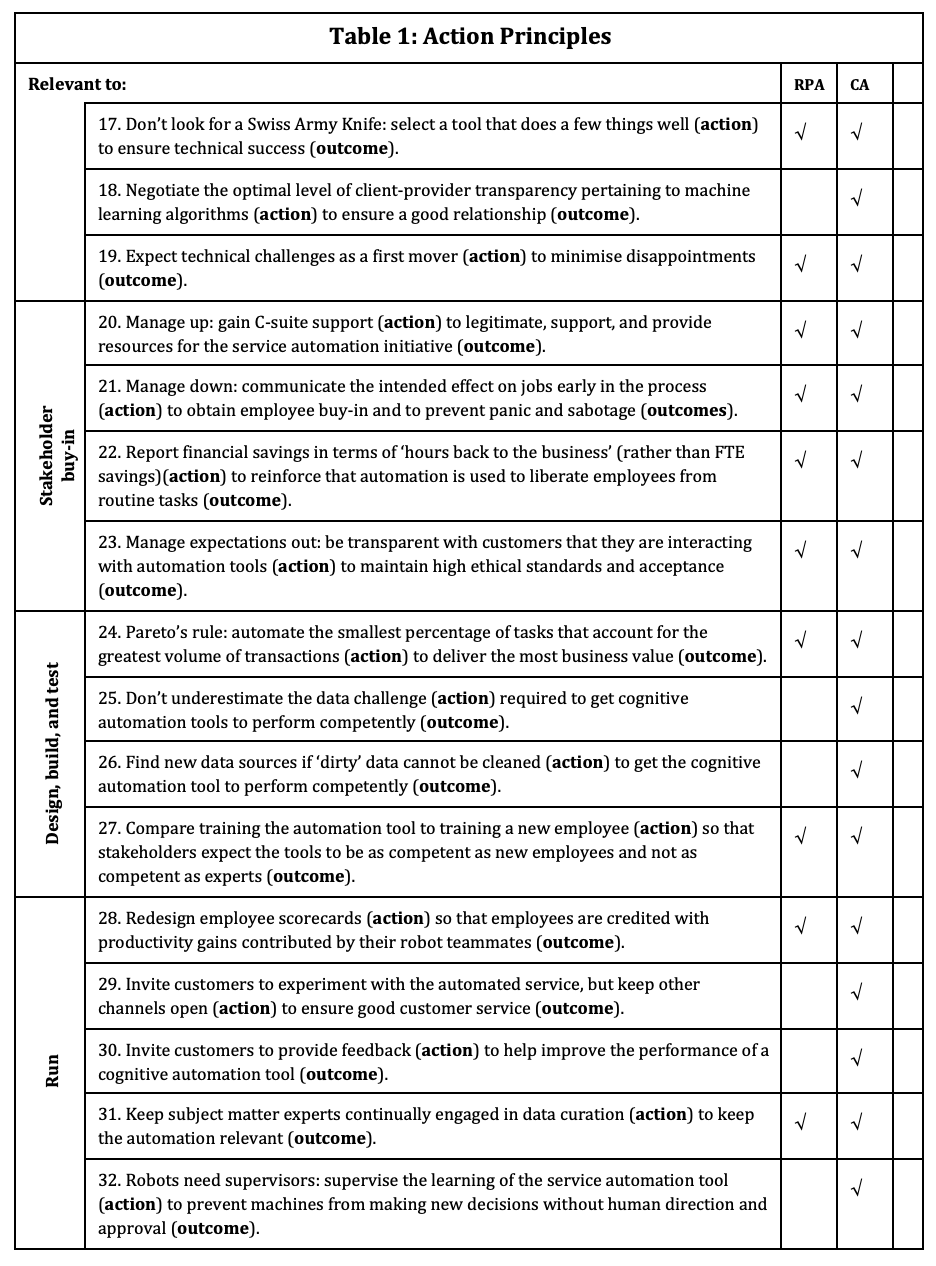

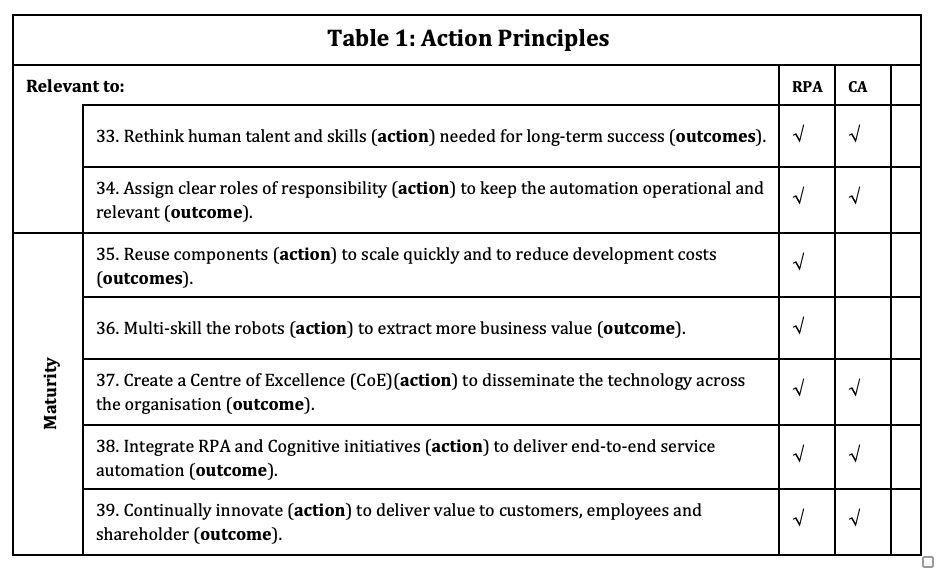

Table 1 shows the most recent product of our analysis: 39 action principles gleaned from all of the data. Note also that a structure emerged; we organised the action principles along the adoption journey phases of Strategy; Sourcing Selection; Program Management; Tool Selection; Design & Build; Run; and Maturity. We also have a ‘General’ action principles category.

It is useful to point out how action principles evolve with more data collection. For example, we initially identified the action principle ‘Let business operations (BO) lead’. After looking at more cases, that action principle was changed to ‘Let business operations (BO) lead, but bring in IT early’. With the next round of data, four new client adoption journeys (IBM, VHA, a financial services firm and an insurance company) had been successfully led by IT. Two of the IT-led cases were automating IT processes (help desk ticketing), not BO processes, which makes sense for IT to lead. As another example, one detailed survey did not find a statistically significant relationship between the RPA champion (IT, BO, or other) and business outcomes. Our books discuss the nuances and trade-offs of each approach (see the www.roboticandcognitiveautomation.com website), while our Journal of Information Technology article provides a more mature and definitive version of our methods, terminology and results (Lacity, Willcocks and Gozman, 2021). Now have a read through the action principles in Table 1. before I comment further on them.

A number of points arise from this Table.

- 1) Firstly, it becomes clear that automation is an on-going, continually changing management challenge. Even into the so-called ‘Maturity’ phase you are never done with automation. Even in ‘Maturity’ there is always further scaling, and further integration with other digital technologies.

- 2) It also becomes clear that most of the challenges and actions are managerial and organisational rather than technological in character. As a rough guide we suggest the split is 75 percent managerial/organisational, and 25 percent technological. This is important as it is all too easy to get lured into the technology, when the real causes of sub-optimal performance lie elsewhere.

- 3) Business strategy must drive automation investments. You need to go way beyond a short term focus on cost and efficiency if you are going to get the automation dividend. We think that to this day roughly 70–75 percent of the value from automation is still being left on the table. In difficult times that it a great deal of avoidable waste.

- 4) Most successful organisation take strategic and operational control of their automations, and use consultants and automation suppliers as advisers and resources. You really do need to build internal core automation capabilities.

- 5) Stakeholder buy-in and change management are keys to success and the most under-invested areas in the automations we have researched.

- 6) Most organisations face real challenges getting their data and processes in good shape for automation. These problems grow the more an organisations moves into more advanced, integrated technologies. There are some great intelligent automation solutions coming forward—imaginative, powerful, and very fast—but none of them are or are likely to be panaceas.

- 7) You do have to form and get used to an ethos of continuous updating and innovation. The exponential data explosion is accelerating, as is the pace with which new more advanced technologies are becoming available. Yesterday’s solution and ways of working can all too easily become tomorrow’s problems. Automation leaders innovate continuously, laggards declare minor victories too early, while others still struggle in the foothills of automation and get left years behind.

Conclusion

Our research-into-practice approach produces action principles, which are practices that explain the results found in real-world implementations. Action principles are anchored in data, reviewed by participants, and offered by other practitioners for consideration when they embark on their own adoption journeys. However, we want to stress here, as we did in an earlier blog that action principles are NOT ‘best practices’. To reiterate, whereas ‘best practices’ imply that mimicry will always produce similar results—that ‘one-size-fits-all’—action principles recognise that context matters.

We view practitioners as thoughtful agents that are best to decide whether an action principle would be effective in their own organisation and situation. The usefulness of a practice depends on:

- • The objectives the organisation is trying to achieve

- • The organisation’s unique context

- • Whether the organisation has the retained capability to implement the practice effectively

- • Timing—there are good and less good moments to apply a specific practice.

References

Lacity, M. & Willcocks, L. (2018a). Robotic Process and Cognitive Automation: The Next Phase, Stratford-upon-Avon, SB Publishing.

Lacity, M. Willcocks, L. & Gozman, D. (2021). ‘Influencing information systems practice: The action principles approach applied to robotic process and cognitive automation’. Journal Of Information Technology, 36, 3, 216-240.

Willcocks, L., Hindle, J. & Lacity, M. (2019) Becoming Strategic With Robotic Process Automation. Stratford-upon-Avon, SB Publishing.