Leslie Willcocks

Professor Emeritus

London School of Economics and Political Science

We are exploring the idea of potential backlashes against technology. Many are expressing anxiety about AI at the moment. But automation anxiety is not a new concept. Long before Keynes, Greek, Roman, Indian, and Chinese myths posited artificial life, automata, self-moving devices, and human enhancements, all accompanied by visions of power, control, but also potential disaster for humans.

In more recent times, automated power looms displaced textile workers in Nottingham, England, because the technology produced clothing more cost-efficiently. The unemployed workers (the Luddites) began a campaign in 1811 to destroy the technology. Similarly, in Lyon, France, in 1831, textile workers staged an uprising in a silk factory known as the revolt of the Canuts (MHL-Gadagne, 2023). Historical events like this frame, shape, and, when coupled with the introduction of automation in the workplace, continue to reignite the debate about unemployment. But that debate now goes far beyond concerns about job displacement. The result is multiple anxieties about where current technologies are going and their likely impacts.

Automation Anxiety

Automation anxiety is not well defined in the literature. We define it as:

"A widespread, often vaguely felt and expressed concern about the potential negative psychological, economic, and social impacts of automation, historically focusing on job displacement, and extending subsequently into the general fear of being adversely impacted in multiple ways by machines, AI, and ever-advancing digital technologies operating in combination."

Risk and Automation Anxiety

A crucial question with automation anxiety is whether the concern relates to actual or perceptual, felt risks. Sandeman (1993) takes on board this issue, and informs our review:

Risk = Hazard (likelihood x impact) + Outrage

Thus, automation anxiety increases the more an adverse event is likely (e.g., an airport computer crash) and the wider its impact (e.g., terminating European air travel). Such a risk does require a calculation of probability, but it is open to rational calculation. However, much risk outside expert assessment is not driven mainly by this calculative component but by the attention, however induced, the risk receives. This is what Sandeman calls the Outrage Component. The Outrage with which less expertly informed publics regard the event, i.e., the degree to which they prioritise the risk, treat it seriously, and react emotionally to it, can heighten that anxiety much further, or diminish it considerably. In practice, there may be little relation between the imminence and size of a hazard and the level of attention it receives.

What causes Automation Anxiety?

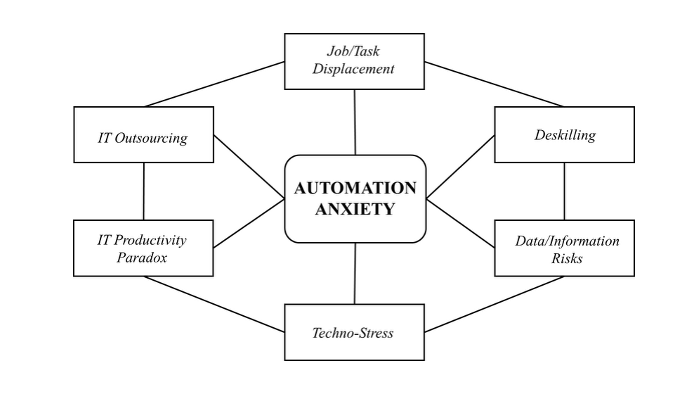

We found six areas where anxieties originate. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. The Web of Automation Anxiety: A Conceptual Framework

Job/task displacement

The major, abiding concern with each generation of technology has been the replacement through automation of parts of, or of whole jobs. Invariably, the media and some studies have, across 1960–2025, regularly produced major ‘outrage,’ ‘hope and fear’ headline narratives on job loss through automation, without giving much detail of the qualifiers, or the fact that the statements are invariably loose predictions rather than facts.

The more careful major studies of job/task displacement and deskilling across the decades of modern computing up to the AI of today invariably add qualifiers (Autor et al., 2018; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2017). These include: the need to add in jobs created through automation, it will be mostly part of jobs rather than whole jobs that will be changed, the imperfectability of the technologies, the need for human-in-the-loop work designs, time taken to institutionalise the technology, and prevailing skills shortages in the top 21 global economies to which automation can be a coping remedy. One study shows the amount of work to be done is not remaining stable but, for a range of reasons, is increasing across the developed economies at between 10 percent and 15 percent per annum. Thus, in practice, the consensus is that if 18 percent of jobs stand to be lost through automation between 2020–2030, 17 percent will be gained, i.e., a resulting net job loss of one percent.

Deskilling

Studies reveal skills shifts over the 2018–2030 period, which are more impactful than in previous eras. As a predictive summary for 2020–2030,

With misleading statistics and narratives, and complex changes and likely dramatic shifts, together with uncertain impacts, it is not surprising that automation anxiety on task/job displacement and deskilling has been rising dramatically.

IT Outsourcing

IT outsourcing literature spans several decades and illustrates a range of automation anxieties among clients and suppliers

There are up to 25 positive reasons for outsourcing; however, a range of studies also report adverse anxieties and outcomes for diverse stakeholders, including:

Our own recent study found that outsourcing had been greatly impacted by developments in the digitised flexible contractual organisation whereby the range of tasks, services, and parties contracted out, including remotely, had greatly increased, with concomitant expansion in risks perceived and actual.

Data/information risks

Automation anxieties arise from the risk of harm or loss from the accidental or deliberate misuse, destruction, or unauthorised access to data and/or information. Two early anxiety areas, subsequently spawning several industries, were information security and data/information privacy.

The threats and anxieties have only grown with the ubiquity of data storage and the accelerating proliferation of information. Thus, approximately 90 percent of the world’s data has been generated within the past two years, and according to IDC, the volume of data stored globally is doubling approximately every four years.

In terms of the Sandeman risk formula, more data/information increases both the likelihood of a risk occurring and the size of its impact. Moreover, within the current social media and communications environment, the ‘outrage’ – i.e., the amount of attention and seriousness assigned to that risk – is also likely to be amplified considerably, thus feeding automation anxiety further.

There are certainly multiple risks to be concerned about:

The underlying anxieties relate to a point made throughout the history of ever-evolving technology: Does can necessarily translate into should? A related anxiety then arises: how far can and should we regulate and set guardrails for data/information risks, with the added complexity that computer-based and digital technologies have developed at such speed that, invariably, regulation lags what it is trying to control?

Even this brief overview reveals how the overwhelming volumes of data and information can give rise to significant anxieties. The tsunami effect often manifests as data/information overload and a sense of lost control. Furthermore, uncertainty surrounding emerging risks may further amplify the anxieties associated with data and information.

IT productivity paradox

As a phrase, this was first used in macroeconomics by Solow (1987) to refer to IT appearing everywhere except in the productivity statistics. Here we use it more generally to circumstances where automation offers solutions but also counter-productive problems, which possibly not only nullify the advantages gained but create a net disadvantage.

The major studies here suggest this to be a perennial concern about computer and digital technologies, with productivity showing up in the 1990s and at other times disappearing and becoming attributable to IT again later Willcocks & Lester (1997) found the main reasons for the paradox were mismeasurement, organisational variations in IT performance, associated soft gains in value that are difficult to estimate, and challenges in implementation. We suggest that these technologies need a suitable organisational and technical infrastructure, plus organisational learning, to be rendered productive over longer time scales than analysts are willing to study.

Techno-Stress

Brod (1984) provided an early overarching definition of techno-stress for our purposes as "a modern disease of adaptation caused by an inability to cope with the new computer technologies in a healthy manner”.

Subsequently studies describe examples of negative stress at first caused by communication devices such as computers, smartphones, tablets and subsequently also by software programs, algorithms, and newer digital technologies.

In the studies, potential causes of techno-stress include: the speed at which technologies evolve; rising work intensity; the opacity and ‘black box’ character of systems, algorithms, information, and decision-making; technical reliability/design issues; computer complexity, technology dependence, and increased computer monitoring.

People often experience stressed behaviours such as pressure to respond in real-time, multi-tasking, a need to stay connected, constant screen-checking, and frequent sharing of updates. Emotional aspects often emerge, such as depression, frustration, irritability, guilt, and/or fear, leading to computerphobia. Psychological stress can arise from information overload, being always connected (‘techno-invasion’), feeling threatened about losing jobs and by people with superior technical understanding (‘techno-insecurity’), constant changes and upgrades leaving people feeling inexperienced and outdated (‘techno-uncertainty’), and where the technology and systems are experienced as complex and intimidating, and thus stressful.

There are now cyber-pyschologists that study these forms of techno-stress a very good source being Mary Aitken’s The Cyber Effect.

But it is very clear that techno-stresses are not the only sources of anxiety generated by advances in digital technologies.

Next time we will explore how these six causal areas have developed over the 65 years that organisational computing has been with us.