- 2025

- September

Leslie Willcocks

Professor Emeritus

London School of Economics and Political Science

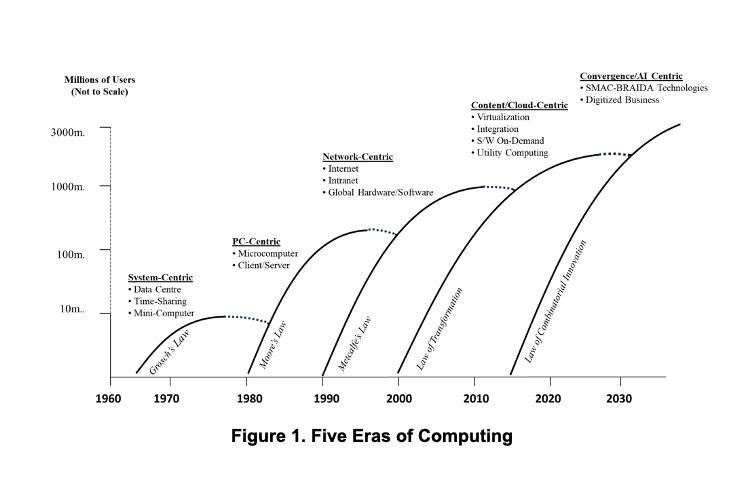

In this blog we are looking at five eras of computing going back to the 1960s to see how automation anxiety developed and the directions it has taken as the technologies have changed and expanded their dominions. Wendy Currie—professor and editor in chief of the Journal Of Information Technology—and I developed this map to help us navigate through what we have identified as five main areas of computing. Each has its own underlying economics.

Grosch’s Law: ‘Computer power increases as the square of the cost,’ meaning that a computer that is twice as expensive delivers four times the computing power.

Moore’s law: ‘Semi-conductor price-performance would double roughly every two years.’

Metcalfe’s Law: ‘The cost of a network rises linearly as additional nodes are added, but the value can increase exponentially.’

Law of Transformation: ‘A business needed to become more bit, as opposed to atom, based. Its transformation would be equal to the square of that of the percentage of that industry’s value added that is bit rather than atom based.

Law of Combinatorial Innovation: ‘The increasing combination of digital technologies in new ways will grow value exponentially.’

Three Observations

1. First, an era marks out the start-up and growth to mass use of information-based technologies. Technological deployment in an era may rise and decline, but in practice, much continues and is built upon during the next phase. Mainframes and PCs, for example, are still massively used today. The Internet and World Wide Web took off in the 1990s and have not stopped growing exponential. The Cloud infrastructure of 2025 was put in place over 30 years. The technologies coming on stream from the 2020s will become increasingly embedded.

2. Noticeable across the eras is the scaling of technological take-up, from millions to hundreds of millions and billions of users (e.g., social media, mobile, cloud) with correspondingly wide-ranging, even global impacts, including for automation anxiety. Not surprisingly, automation anxiety has increased correspondingly across the eras along with the rising power, disruption, and impact these computers and digital technologies have brought with them.

3. Major technology investments, including into automation and AI, rarely pay off quickly. The historical adoption rates for various information, communication, and digital technologies have been analysed, highlighting trends in how these technologies diffuse across societies. Once commercially available, with notable exceptions, technologies still take between 8 and 28 years to achieve 90 percent adoption in the developed economies (for the Manyika study, the range for 50 percent adoption was between 5 and 16 years). Thus, our dating of the eras is representational, reflecting this kind of evolution, and eras overlap at many points. From the analysis, we arrive at a combination of findings and patterns that further our understanding of automation anxiety.

A number of patterns emerge:

1. The Recurring Job Loss Fear

Automation anxiety discourse pervaded across many decades of the 20th century, with much of the debate centring on job/task displacement. An automation crisis in the 1960s created a surge of alarm over technology’s job killing effects, especially in the USA. Historical precedents of the creative/destructive impacts of technology have considerably shaped present debates, expectations, and anxieties.

Undoubtedly this psychologically framed subsequent technological developments as anxiety inducing. The following decades have seen the rise of internet-based, intelligent technologies, new forms of work through digital platforms, flexible work regimes, and novel human-machine augmentation. In the 21st century, machines and automation continue to fuel discourse about employment and job loss.

Job/task displacement is psychologically linked to technology and impacts the collective imagination. This creates an instinctive fear of new technologies and leads to a transference of what may be multiple anxieties into the one concrete possibility of ‘job loss’. It has become the ‘idee fixe’ of any debate about technology, regardless of the real likely impacts on work.

2. The Technology–Regulation Lag

Over the past 65 years, the advancement of computing technologies has consistently outpaced efforts to regulate their development, usage, and societal impacts. By 2005, the technology regulation gap was commonly perceived as up to seven years depending on the issue. We have seen the timelines and disparities have only grown much larger as the technologies have become more complex and impactful, and the stakeholders more numerous, anxious, and often more litigious.

One fundamental regulatory concern throughout has been to strike a balance between stimulating innovation and protecting the interests of different stakeholders, human rights, and societal well-being. This balancing act has proved challenging globally.

Awareness of this growing technology regulation gap greatly increased across the first 20 years of the 21st century, has come to a head and converted into serious automation anxiety. This has focused, possibly disproportionately (‘Outrage’ at work). The European Union has, since the early 2000s, promoted various kinds of IT/digital regulation, despite complaints from technology vendors and those favouring more market-based solutions. But in the face of rising automation anxiety about AI, its regulation is likely to increase rather than decrease.

Regulators are left with trying to achieve a difficult balance between safeguarding safety, fairness, and transparency while fostering innovation and responsible adoption. Effective implementation could reduce anxiety amongst many stakeholders, but increase anxieties amongst others, while imperfectly applying the rules could have unanticipated consequences for stakeholder automation anxiety levels. There are many other regulatory and advisory initiatives designed to ameliorate AI anxieties, though few are as wide-ranging and enforceable as the EU legislation.

3. The FoMO Factor

In common usage, FoMO stands for ‘fear of missing out’. According to Gupta and Sharma (2021, p.4881), fear of missing out:

“…is a unique term introduced in 2004 to describe a phenomenon observed on social networking sites. In 2013, British psychologists elaborated and defined it as a “pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent”.

In this latter sense, we can observe recurring FoMO when applied not just to social media phenomena but to emerging new technologies generally. Thus, FoMO feeds into automation anxiety. While computer-based technologies have always been heavily marketed across the 1964-2025 timeline, it was only when selling moved into the mass PC market from the 1980s on that FoMO began to arise amongst consumers. Looking retrospectively at how marketing technology products worked, FoMO was an important part of this marketing play throughout the 1980s, and can also be observed, by way of examples, with the internet from the early 1990s, e-business in the late 1990s, mobile phone take-up in the 2000s, enterprise resource planning systems from the 1990s, social media, cloud storage, and more recently ChatGPT and gAI.

Conclusion

There are two other insights we will deal with in future videos.

One concerns the immense hype that occurs at the beginning of each new era. We will look at that in a later video.

But first in the next video we will examine AI, which is being heralded as ushering in an ‘unprecedented digital future’ but in fact we have heard this rhetoric many times before.

Stay tuned, and see you next time!