- 2026

- January

Leslie Willcocks

Professor Emeritus

London School of Economics and Political Science

An ancient and well-developed narrative supported by historical events concerns the power, transformation, and peril brought by technology.

During our second and third eras, this belief fed into a second story emerging of an ‘unprecedented digital future’ induced by computer and digital technologies. Enough evidence, vested interests, and anxiety developed to lend credibility to predictions of even greater advances, together with immense, both positive and adverse consequences.

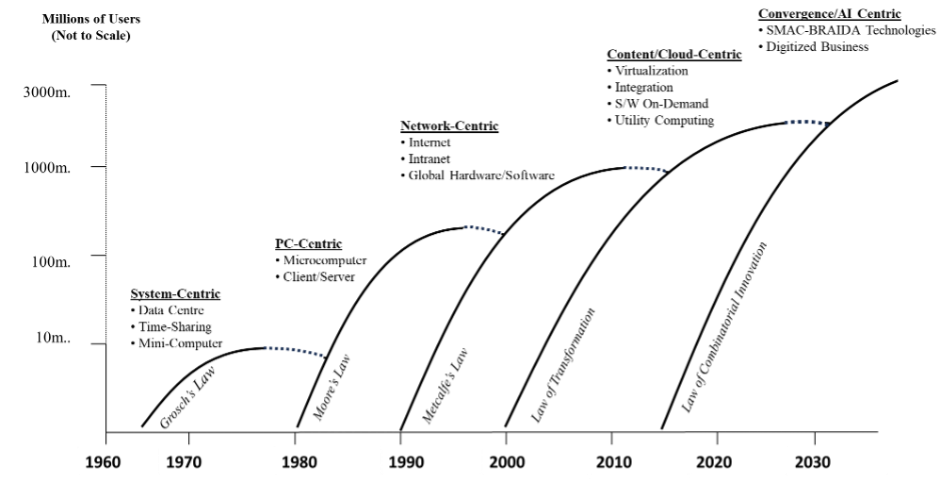

Figure 1 - Five Eras: An ‘unprecedented digital future’?

With the Internet bubble of 1993–2001, these claims began to polarise into utopian and dystopian scenarios. For example, on the pro-technology side, Kurzweill (2008) posited the coming of a Singularity when computers and AI supersede human abilities (AI outperforms human intelligence around 2029) and combine with human capacities (around 2045), leading to a bright techno-future. This and similar viewpoints provoked automation anxieties and a string of more dystopian views.

Across the 2001–2025 period, these narratives subsequently accelerated. Post-2015, they increasingly focused on ‘AI’. Accordingly, Scientists for Global Responsibility (2018) published results of a member survey where over 80 percent perceived a medium to high chance of things going badly wrong with AI, while 96 percent wanted more AI regulation, and 82 percent thought that AI was more likely to create a dystopian rather than a utopian future. Such views entered the public imagination, with many influential voices, fearing the worst, expressing concerns about how to keep AI socially responsible.

Across the 2015–2025 period, as a third narrative, AI became the poster child to represent all automation, and so automation anxiety has crystallized into AI anxiety, a container of all digital ‘superagency’ but also its perils and potential disasters.

These three narratives are the major components of what has become what we would call ‘the unprecedented digital future’ meme, reiterated, utilised, and magnified variously by journalists, social media users, hi-tech vendors, government reports, academics, and citizens alike.

This motif is powerful partly because there is clear evidence of dramatic advances in technology, its capabilities, and impacts. However, invariably it is not accompanied by considerations of how much stays the same, including with technology, what has been called ‘the shock of the old’. Moreover, digital technology is not the only or even main force impacting the future. Atkinson and Moschella (2024) also point out that the 1900-1960 period experienced technological and other innovations across industry, work, and society that had much more profound impacts than those of the following years. They also show that the pace of technological change is not accelerating, and suggest that overestimating the speed leads to exaggerations, fears, anxieties, and an anti-innovation mindset.

Thus, today’s concerns display an ahistorical, recency bias that contributes to much additional, perhaps unnecessary anxiety about the future. This is not helped, of course, by the increasingly dynamic, interconnected, uncertain global context of the 2020s in which societies and businesses find themselves.

Against this background, media/social media, consultancies, and technology vendors have regularly heralded each emerging digital technology as distinctive, unprecedented, and ‘breakthrough’. Looking across our five eras of computing, one can see this, for example, with the internet, mobile phones, social media, blockchain, cloud, more recently AI, and, from 2023, ChatGPT.

Across the five eras, it becomes evident that the widespread sharing and acceptance of this meme have heightened automation anxieties.

This prognosis of an unprecedented digital future is very connected with the immense hype that has heralded modern digital technological progress. Our final video will look at how this hype has peaked with AI, and how the influential so-called Gartner hype cycle, far from helping to predict the future, has, since its emergence in the mid-1990s, only probably enhanced the hype.